There is a singular joy in reading immigrant novels that interrogate the idea of home, especially when explored as an ache or memory one returns to and remakes to suit desires. Migration, displacement, and the search for a place to belong are often the soul of these stories, especially when written with care and complexity.

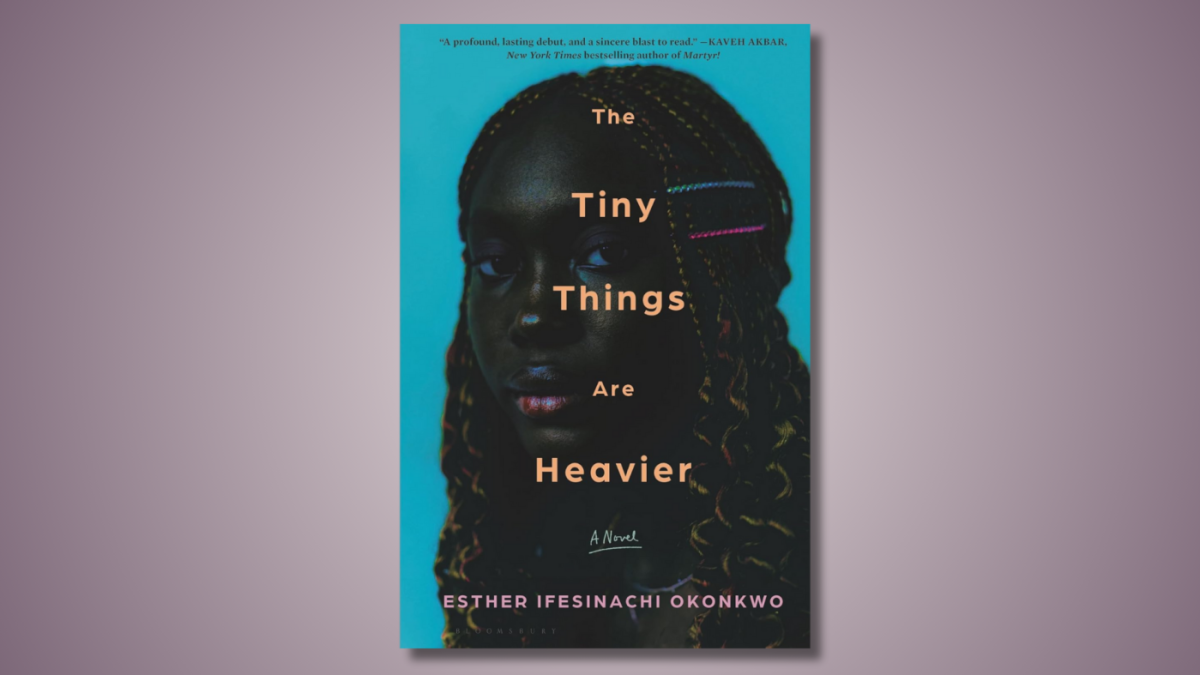

With her debut novel The Tiny Things Are Heavier, Esther Ifesinachi Okonkwo takes her place among the writers who have done it well.

At the center of this story is Sommy, a Nigerian graduate student who has just arrived in Iowa, carrying the guilt of leaving her brother Mezie behind in the aftermath of his suicide attempt. She is homesick, disoriented, and straddling two geographies with a deepening sense of dislocation. She develops a confusing bond with her Nigerian roommate, Bayo, and begins a romance with Bryan, a biracial American man estranged from his Nigerian father. Sommy’s relationship with Bayo materializes as she clings to the familiarity of home, especially as her brother refuses to communicate with her when she tries repeatedly to reach out to him. She sees a lot of her brother’s ambition in Bayo as he eagerly consumes everything America has to offer, while Sommy seems to flail aimlessly. Sommy, Bayo, and Bryan’s relationships become a framework through which the novel explores race, grief, and the fragility of family and intimacy. Their interactions are often rooted in longing, estrangement, and cultural tension.

Okonkwo’s prose is measured and deliberate, echoing the rhythmical storytelling style of Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. The comparison is almost impossible to ignore in the early chapters, where the tone, narrative restraint, and contemplative interiority feel unmistakably Adichie-esque. But as the story deepens, Okonkwo’s voice begins to assert itself in her own version of being very controlled, observant, and emotionally precise.

One of the novel’s strengths lies in its portrayal of how Black immigrants encounter race anew in America. Sommy’s arrival in the country is marked not by excitement, but by rupture: A racial encounter with a white woman and her child that instantly marks her as “other.” It’s a scene that draws a line in the sand between her romanticized ideas of America and the country’s more jarring realities. Sommy’s perception of class, race, and selfhood is further upended by the most casual exchanges, like when a white classmate attempted to “translate” Sommy’s argument in one of their classes. “Glad that someone here speaks African,” Sommy snaps at the brunette, wishing that she reacted that way to the white mother who scolded as well. By then, Sommy is disillusioned and sees almost every interaction she has with another race as a possible combat field, as many Americans do. These moments accumulate like time weights, dragging her further from the certainty she once had about her and the world.

Her relationship with Bryan eventually becomes the crux of the narrative. Bryan, despite being biracial, is American in posture and perspective, steeped in a privileged version of Black identity that often feels inaccessible to Sommy. He cannot speak her language, literally and metaphorically, and his understanding of Nigeria is filtered through distance and avoidance. He doesn’t understand her family ties and sees her relationship, or lack thereof, with them in shades of Black or white. Bryan also has his issues with being recognized as a Black man in America. Their dynamics are complicated, tender at times, but never quite balanced. Sommy is caught between wanting to belong, even to Bryan, and resenting what that belonging might require her to sacrifice.

Sommy eventually convinces Bryan to visit Nigeria to search for his father and find his own sense of belonging. This trip, the second part of the novel, is where the differences in Black culture are laid bare — American vs. Nigerian — and where Sommy begins to notice just how much America has subtly influence her way of thinking: “Had Mezie become one of the Africans who referred to Africa as though it were a country? Or had she become one of those people who read power imbalances in every interaction?”

Okonkwo’s characters are bold, sometimes even theatrical in their attempts to adapt — Sommy trying to fit in at school, Bryan attempting to shed his privileged background to seem more “Black.” Bayo is especially interesting in this regard. He is sociable, performative, seemingly at ease in white spaces, but also deeply insecure, constantly seeking validation. Through him, Okonkwo explores the subtler humiliations of assimilation, such as the small ways one must contort oneself to fit into a country that rarely makes room for difference.

While The Tiny Things Are Heavier doesn’t push the genre in radically new directions, it offers an intimate, resonant portrayal of a young woman caught between two worlds she desperately wants to be a part of. The “tiny things” of the title are not merely metaphorical, they are the unspoken tensions, cultural misunderstandings, emotional burdens, and quiet betrayals that accrue in every immigrant story. Okonkwo writes with a calm confidence, where she refuses to rush her revelations. And by the end of the novel, we are reminded that what weighs us down most isn’t always the trauma we left behind, but the identities we try to build or abandon in the name of survival.