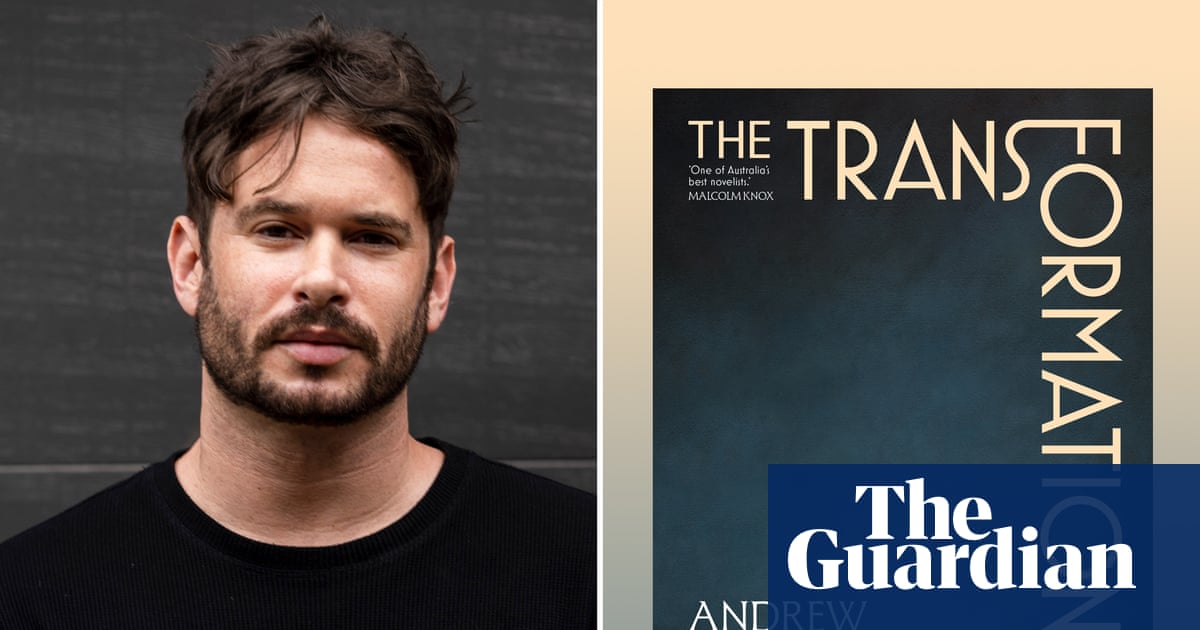

Andrew Pippos’s debut novel Lucky’s charmed readers with its fusion of Greek tragedy and multigenerational heft. Five years later, he has navigated the notoriously difficult expectations around second novels with aplomb, delivering a sensitive portrayal of professional and personal change, albeit on a smaller canvas.

The Transformations is set in Darlinghurst in 2014, in the newsroom of a fictional broadsheet newspaper, the National. Pippos’s focus is on amiable everyman George, a 35-year-old subeditor who works the night shift. After six years with the paper, he’s yet to become as jaded as some of his colleagues, and ekes out a conscientious living as part of the production crew. He takes pride in his job and his industry, marvelling at how “everyone in the newsroom was engaged in the incredible task of describing the world each day”.

Pippos explores the print newsroom with nostalgic fondness, a nearly bygone world that’s slowly devolving into obsolescence and captured here as though in aspic. The lively open-plan space with its “smell of decomposing inks and solvents”, TV sets suspended “like pendants” and the nearby sanctuary The Nobody, the shabby-not-chic pub that the journos repair to after a punishing day (and night) wrangling copy.

Individual portraits of the National’s motley crew are lovingly drawn with a verisimilitude that stems from first-hand experience (Pippos has worked in the paper trade). From the proprietor and editor-in-chief, to the foot soldiers of news-gatherers and correctors, Pippos’s insightful snapshot portraits of George’s colleagues, from fellow subeditors to reporters on the death call, reveal the ethos and challenges of print journalism.

The book opens with the departure of two of George’s colleagues, harbingers of the precarity facing the industry. But for the time being, George is safe. Unassuming and unobtrusive, he’s the classic avoidant personality type, for whom solitude is in service to self-protection: “He saw the world as fundamentally inscrutable and malignant and he had reason for this prejudice.”

It takes Cassandra, a senior reporter at the National, to disrupt George’s equanimity. The book’s title refers not only to transformational changes in the media, but also to the shifting emotional landscape between Pippos’s two protagonists. Their story starts shakily: Cassandra is married with two young children and is experimenting with polyamory; George, meanwhile, is dealing with the unexpected arrival of his teenage daughter, Elektra, whose mother, Madeleine, is returning to New South Wales after a stint living in Victoria. There are twin challenges for George, who must become an active father to a child he did not raise, and wants to be a partner to a woman he’s not married to.

Through third-person omniscient narration, The Transformations follows George and Cassandra’s convoluted course towards sustained friendship and love as they weave in and out of each other’s lives. There is forever a tension between honouring their own happiness and the compromises that must be considered when others are involved. This is the heart of the novel: the push and pull between personal desire and familial obligations. And Pippos’s attention to all his characters makes it easy for the reader to care about them, or at least understand their motivations.

after newsletter promotion

At times The Transformations veers close to sentimentality, and the ending is perhaps a little too neatly wrapped up. But it is a tender book that canvasses myriad issues: the balance of long-term relationships, parenthood and responsibility versus sexual freedom and individual autonomy; the lasting effects of historic child abuse and alcoholism; and class divisions. Madeleine and her smug wealthy parents, their conservatism and materialism, for instance, are shown in sharp relief against George’s working-class roots – raised by Greek parents labouring around the clock in their steak-and-chips cafe – and Elektra, who is caught between both these worlds and straining to find a voice of her own.

There are some funny set pieces in The Transformations that leaven the stress of a workplace, but the National is a backdrop to the actual drama at play: George’s interior struggles with self-actualisation. His journey to emotional clarity is handled with depth and nuance. Minor characters orbiting the narrative are also finely drawn; Pippos has a knack for dialogue and articulating the messiness of life and relationships.

The Transformations does not have as grand a scope as Lucky’s, which took in several continents and decades of transitions. Instead, this book finds a quieter drama in the struggles of an ordinary man, trying to do the best he can, with the heart he has: humble and bruised and unsure. When George finally takes control and becomes more proactive, rather than reactive, to his circumstances, it makes for an ultimately predictable, but nonetheless satisfying read. The lede in this battler story may well read: against the flux, subeditor changes the script of his life.