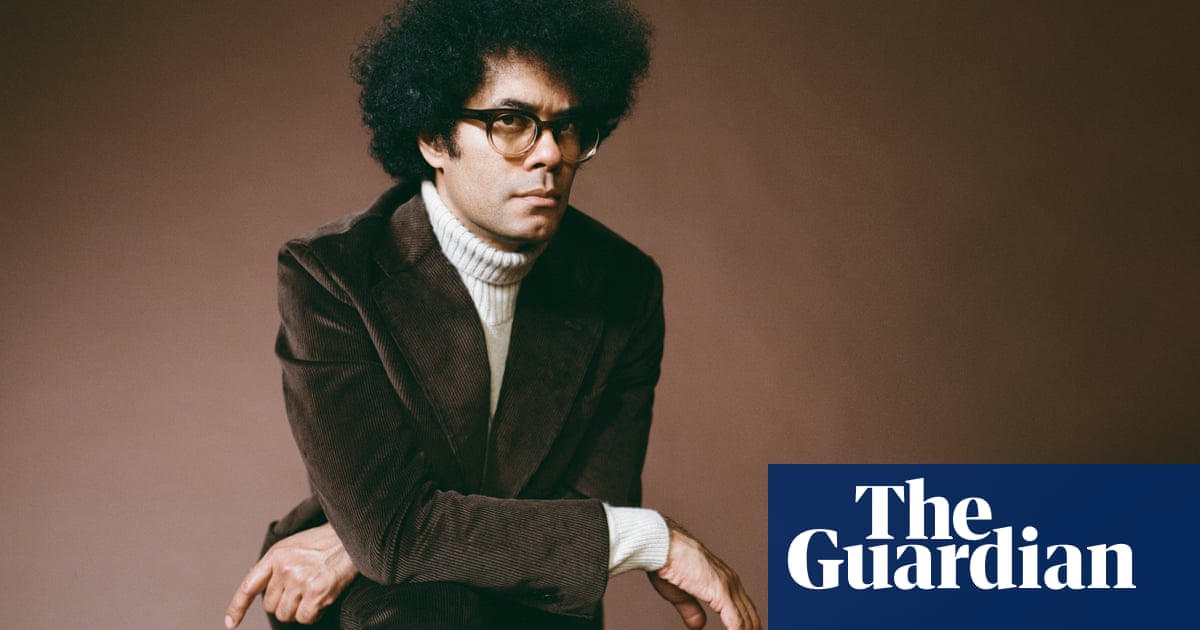

The Unfinished Harauld Hughes is something like a South Bank Show House of Leaves: it’s the narrative of the making of a documentary that never gets made, about a movie that also never got made. Its protagonist-narrator is Richard Ayoade, an alter ego of the author of the book, Richard Ayoade. He’s in search of an alter ego of his own – or, at least, a doppelganger.

The late Harauld Hughes – author of era-defining plays with titles such as Platform, Table, Roast, Roost, Prompt, Flight, Shunt and Dependence, and subsequently a hack screenwriter – is Ayoade’s white whale. It so happens that the playwright’s author photograph looks extremely like Richard Ayoade, except that Hughes “wore the kind of glasses I would search for, in vain, from that moment on”.

Ayoade’s interest in Hughes, kindled by the chance likeness, develops into a deep reverence: “Harauld Hughes, to my mind, is drama.” Now, for sheer love of Hughes (he reproaches himself, from time to time, that he should never have agreed to make this documentary), Ayoade is filming an arts programme to be called The Unfinished Harauld Hughes, in which he trundles around interviewing such associates of the late playwright as will agree to talk, and goes in quest of a copy of O Bedlam! O Bedlam!, Hughes’s last, lost film. The footage is apparently in a Swiss bank vault somewhere, and nobody who knows about it is prepared to say anything that makes a lick of sense.

What tips this from being a comic novel into something more like a conceptual art project is that, foolishly or heroically, Ayoade has actually written the complete works of Harauld Hughes, in three volumes – Four Films, Plays Prose Pieces Poetry and The Models Trilogy – released, apparently, as limited editions, alongside the novel. So you can now read or even perform Platform, or The Awful Woman from Space. They come with straight-faced prefaces, timelines, deleted scenes, critical essays, the lot. That’s a degree of commitment to world-building George RR Martin could learn from.

The fictitious Hughes has very much more than a dollop in him of Harold Pinter. He’s angry and shouty (“the most furious British writer since the Boer war”), he’s famous for his dramatic pauses, he has a roughish East End background, and he has a troubled first wife whom he leaves for a bit of posh (if that’s not too disrespectful an epithet for the many-splendoured Lady Antonia Fraser or, in this case, Lady Virginia Lovilocke). But there are differences, too. For Pinter’s fabled love of cricket, substitute a fierce interest in badminton.

Why badminton? The same reason, I suspect, why “Harauld”, and why the facial likeness between Ayoade and his subject. Because it’s funny and a bit offbeat and random, and why not? Ayoade’s book is full of such touches of mild absurdity. Its comic tenor is part satirical and part pure whimsy, and it’s very beguiling.

In the satirical mode, as he travels from interview to interview with pretentious Director Dan, Tony Camera and a stoner soundman called Wiggsy, Ayoade is excellently droll on the making of presenter-led telly “docs” (it bugs our hero that Dan calls them that, but telly people undeniably do). For Dan’s purposes, naturally, Ayoade is on a journey. Dan’s way of keeping the sense of a journey is to show a journey, bookended by someone saying they are about to go on a journey and/or have just been on a journey, all the while staring at a moving landscape through a reflective surface, underpinned by a voiceover about being on a journey. His commitment to literalism is almost inspiring.

The journey, it’s probably not too much of a spoiler to reveal, goes nowhere. As tempers fray, interviewees drop out or die unexpectedly, and promising leads turn out to be dead ends, Tony Camera rants: “How are you meant to journey through the life of a writer. They don’t do anything – they don’t fight wars or make laws or save lives, they just make shit up!”

But it’s not the journey. It’s the friends we make along the way, right? Those friends include the excellently imperious Lady Virginia, Hughes’s East End associates (who have about them more than a touch of Monty Python’s Piranha Brothers), a pompous theatre critic and, of course, the splenetic Hughes himself. Ayoade’s quietly intelligent, low-key wit, funnelled through his hangdog narrator, makes this a journey worth taking.

after newsletter promotion