Fiction

A thrilling novel of ideas

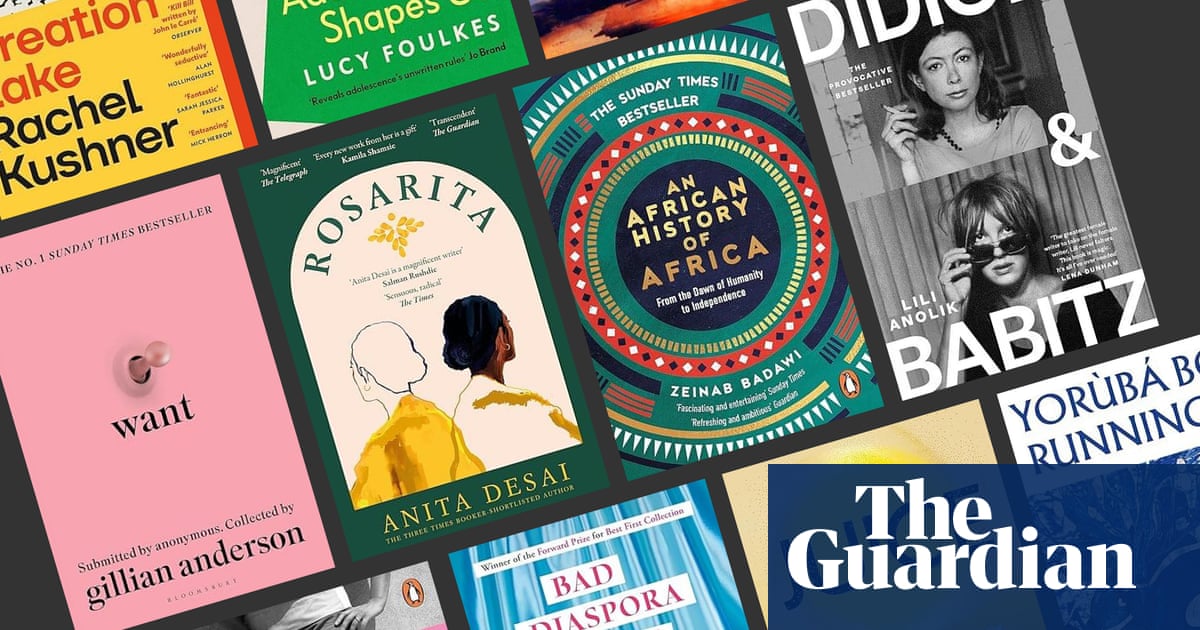

Creation Lake

Rachel Kushner

Creation Lake Rachel Kushner

A thrilling novel of ideas

Bruno Lacombe, in his youth an ally of the 1960s revolutionary intellectual Guy Debord, is now self-exiled to a cave complex in the limestone regions of southern France. The caves are like a kind of political rhetoric in themselves, a message convoluted and endless. Their vanished inhabitants obsess him. Since the Neanderthal extinction, “the wedge between human beings and nature” has become “far deeper than the wedge between factory owners and factory workers that created the conditions of twentieth century life”. The left, he believes, needs to properly understand this.

Meanwhile, shadowy French authorities have decided that Lacombe and the “Moulinards” – the post-Debordian eco-commune he mentors by email – need to be steered out of their less than utopian rural domesticity and towards some act of serious terrorism, so they can be dealt with. So they hire Sadie Smith, a freelance American spy-cop, to infiltrate and provoke an outrage. The situation Sadie finds on the ground is confused and intersectional, centred on a real-life green issue: the diversion of local water supplies into vast “mega-basins” to support corporate agribusiness projects at the expense of the local farmers and the environment. Actors within and without the Moulinard commune, less in bad or good faith than in something shifting constantly between the two, all have their motives for protest or intervention.

Sadie is a triumph of character – not quite fully self-deceived, not even entirely corrupted by the barely controlled confusions, emotional complications and near-disasters of the deep-cover agent’s life. She’s a satire, but she’s also being straight with us. She’s not quite a sensationist, although the world pours in on her senses, and through hers into ours. How, Rachel Kushner asks in this Booker-shortlisted novel, does the individual’s embrace of experience interface with the ideological? In what circumstances can ideology even permit an interface? Sadie Smith is perhaps both question and answer.

M John Harrison

Psychology

The truth about teenagers

Coming of Age

Lucy Foulkes

Coming of Age Lucy Foulkes

The truth about teenagers

What does your reminiscence bump look like? If this sounds like a blow to the head with a touch of amnesia, it isn’t – but it might be just as painful. No, as Lucy Foulkes explains in her eye-opening guide to the psychology of adolescence, it’s the period of life during which people report the greatest number of important autobiographical memories. For most of us it starts around 10 and peaks at 20, taking in a plethora of firsts: first kiss, first love, first time drinking alcohol or taking drugs, first time away from home. Not to mention exams, bullying, breakups and bereavement. Thinking about it, maybe a concussion would be preferable. But then, as this book shows, it’s these enduringly vivid years that define the adults we become.

Foulkes, a research fellow in psychology at the University of Oxford, conducted 23 in-depth interviews for Coming of Age and they are by turns funny, hair-raising and desperately sad. Occasionally, like Naomi’s account of her first love, Peter, they have a sort of novelistic potency. In any case, the majority of readers will find someone they can identify with among her diverse cast of teenagers. Most are now in their 30s or older and are looking back wistfully, with regret, or with something like equanimity. Their accounts allow Foulkes to bring out her central point: that we narrate our lives into being, and that adolescence is so important partly because it is where this narration begins in earnest. The stories we tell ourselves shape who we are, and we can get stuck in these stories, or change them to our advantage.

Coming of Age ends movingly. Foulkes showed each of her subjects what she’d written to make sure they were happy with how they’d been portrayed. These were stories of joy, pain and loss that had reverberated through their lives. For many, seeing them presented as part of the broader story of adolescence prompted a re-evaluation. One said their “shoulders had finally dropped” after 20 years, another that they now felt ready to talk to others about what they had been through. Adolescence may be the first draft of personhood, but it doesn’t have to be the last, as this wise and revelatory book shows.

David Shariatmadari

Geopolitics

Minute by minute account

Nuclear War

Annie Jacobsen

Nuclear War Annie Jacobsen

Minute by minute account

There is, as Jacobsen says, “no such thing as a small nuclear war”: it would mean the end of civilisation. In this powerful book, she describes in horrifying detail how it could happen today. The US has been preparing plans for a nuclear third world war since at least the 1950s, when the H-bomb was created. This was many times more powerful than the Hiroshima bomb, which killed at least 80,000 people instantly.

By 1960, the US war plan for a pre-emptive strike on the Soviet Union predicted 275 million people would die in the first hour, followed by 325 million more from radioactive fallout. A Soviet counterstrike would have killed 100 million Americans and a similar number from fallout. Someone who was privy to these top-secret plans likened them to the Nazis’ preparations for genocide.

Jacobsen’s deeply researched book consists of a minute-by-minute account of a frighteningly realistic scenario in which North Korea launches a nuclear-armed intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) at the Pentagon in Washington. It is what the US and Russia feared most during the cold war. Each country devised meticulous protocols to ensure their massive arsenals could still be launched, even when their leaders had been killed. Jacobsen shows in chilling detail how these plans would be implemented, from the moment the launch of “the all-powerful, unstoppable, civilisation-threatening ICBM” is detected, to the president’s decision to hit North Korea with 82 nuclear warheads 20 minutes later. But as the US ICBMs have to overfly Russia to hit North Korea, the Russians mistakenly believe they are the target and launch their own missiles at America – a fatal miscalculation for the entire world.

A mere 32 minutes after launch, the North Korean missile hits Washington: “Never in the history of mankind have so many human beings been killed so fast.” Forty minutes later the Russian missiles begin hitting America in a barrage of “nuclear hellfire” that would lead to the deaths of more than 5 billion people. It would also cause a “nuclear little ice age”, destroying agriculture around the world for a decade.

Jacobsen rightly says that “the whole premise of using nuclear weapons is madness”. As gripping as any thriller, her book brilliantly portrays the horrific reality of nuclear war and the threat it continues to pose to the very survival of human life on our planet.

PD Smith

Fiction

A well-mapped romance

You Are Here

David Nicholls

You Are Here David Nicholls

A well-mapped romance

Michael, 42, a bearded geography teacher from York, is walking 200 miles across Britain in order not to think about his recent divorce. His concerned friend Cleo gathers a small party to accompany him for the first few days, including her old friend Marnie, 38, a copy editor, also divorced, living in Herne Hill.

Backstories are gently woven: unremarkable childhoods, how their marriages fell apart, the arc of their careers. Then everyone else goes home, and we are left with Marnie, Michael, their growing sexual chemistry and Britain’s spectacular landscapes.

Nicholls’s novels often confound narrative expectations – most notably with the shock ending of One Day – but there are few surprises here. Short, pacy chapters are energised by a trail mix of jolly headings: in one section, playlist songs that Marnie and Michael share – “Don’t Speak by No Doubt (1996)”, “No Limit by 2 Unlimited (1992)”. Droll signposting aside, we are following the Jane Austen map of romantic plotting: two wounded but complementary souls, initial indifference, misdirected affections, growing attraction, misunderstandings, obstacles, hope and resolution.

There is satisfaction to be taken from this midlife redemption tale, not least because it fills a gap: Nicholls’s novels now cover love and marriage across every age bracket from teens to mid-50s. It may not be challenging – unlike Austen’s Persuasion, quoted in the epigraph, it offers neither visceral desperation nor pent-up agonies – but for many it will be a comforting antidote to the grimness of our grim world, a crowd-pleaser and, surely, a TV hit-to-be.

Lucy Atkins

Letters

Let me be your fantasy

Want

Gillian Anderson

Want Gillian Anderson

Let me be your fantasy

Part of the pleasure of reading Want – a collection of 174 anonymous sexual fantasies submitted by women from around the world – is that the scenarios are often strikingly odd. One contributor dreams of being fed chocolate by the Hogwarts potion master. Another longs to have sex with her office door knob. Women are still seen as less sexual than men, but this book attests to a vivid imaginative hinterland, where the desires are far more inventive than the “Milf” and “cheerleader” tropes that dominate man-made porn. In one particularly detailed submission, a woman daydreams about breastfeeding an attractive cashier at the supermarket.

The fantasies in this book are sometimes shocking, but hard limits were imposed during the selection process to remove anything that, if acted out in real life, would be illegal. Want is edited by Gillian Anderson, who has restyled herself as a sort of sexual agony aunt after playing a charismatic therapist in Netflix’s Sex Education. In her introduction, Anderson explains how she struggled with the less straightforwardly empowering submissions. Some did make the final cut, but they are punctuated by anxious self-justification. One woman interrupts her fantasy about being held captive by a group of robbers to insist that she is “a feminist”, and that the imaginary robbers have her “consent”.

Some of the stories in this book feel too self-censored to be truly erotic. Even so, Want makes for addictive reading. More compelling than the fantasies themselves are the frequent glimpses into the women’s real worlds. One contributor confesses that she fantasises about her partner’s death – she longs to be free, because she has never explored her true feelings for women. Another writes that she brings herself to orgasm by thinking about her husband cheating on her. He has been unfaithful in reality, so every time she does this, she cries. The real-life loneliness conveyed here is much rawer than the wish-fulfilment. At its best, Want gives you privileged access into the most painful, truthful corners of these women’s lives.

Kitty Drake

Fiction

A transcendent late gift

Rosarita

Anita Desai

Rosarita Anita Desai

A transcendent late gift

Anita Desai’s riddling and haunted new novel is set in motion when Bonita, a young Indian woman, meets a tricksy figure in a park in San Miguel de Allende, Mexico. A student of Spanish, Bonita is leafing through local newspapers when she is approached. “The Stranger” – elderly, overfriendly and peculiarly dressed “in the flamboyant Mexican style that few Mexican women assume at any other than festive occasions” – claims to know Bonita’s dead mother, whom she calls “Rosarita”. She says they met and became friends when the latter came to pursue art under the tutelage of Mexican maestros. Bonita has no recollections of her mother painting or travelling to Mexico. She remembers, however, “a sketch in wishy-washy pale pastels that had hung on the wall above your bed at home, of a woman seated on a park bench – and yes, it could have been one here in San Miguel – with a child playing in the sand at her feet”. The woman “is not looking at the child and the child is not looking at her, as if they had no relation to each other, each absorbed in a separate world, and silent”.

Written in the second person, the novel interrogates the gulf that can exist between a parent and her child, and the sketch – forgotten and recalled – is a sly mise en abyme that also speaks to the fickleness of memory, and the ever-porous boundaries between the past and the present.

Desai has been writing for more than six decades now. Thrice shortlisted for the Booker prize, she is known for the effortless lyricism of her sentences, the deceptive simplicity of her stories, and her canny eye for detail. This is a novel of profound philosophical inquiry, pondering the enigmas of the mind and the self, the frontiers of fantasy and reality, and ultimately, whether one person can ever fully imagine and understand the life of another.

Yagnishsing Dawoor

History

An insider’s take

An African History of Africa

Zeinab Badawi

An African History of Africa Zeinab Badawi

An insider’s take

There is no shortage of big tomes about Africa written by old Africa hands – those white journalists, memoirists, travel writers or novelists who know Africa better than Africans. This genre, lampooned by Binyavanga Wainaina’s satirical essay How to Write About Africa, weaves together stories that exalt the continent’s landscape but decry its politics, that revere its wildlife but patronise its people, that use words such as “timeless”, “primordial” and “tribal” when explaining Africa’s historical trajectories.

Zeinab Badawi’s An African History of Africa is a corrective to these narratives. Ambitious in scope and refreshing in perspective, the book stretches from the origins of Homo sapiens in east Africa through to the end of apartheid in South Africa. It is informed by interviews Badawi conducted with African scholars and cultural custodians, whose expertise, observations and wisdom are threaded through the book.

The very act of telling African history from an African perspective and making this history accessible to a wide audience is an assertion of dignity and an invitation to learn more. As Badawi puts it: “I hope I have demonstrated that Africa has a history, that it is a fundamental part of our global story, and one that is worthy of greater attention and respect than it has so far received.” She most certainly has.

Simukai Chigudu

Biography

Friendship and rivalry in LA

Didion & Babitz

Lili Anolik

Didion & Babitz Lili Anolik

Friendship and rivalry in LA

Journalist Lili Anolik’s latest book is a “provocation”, a dual biography of the two friends who carved their initials on to the counterculture of 1960s and 1970s California. Joan Didion used her reporting skills to fashion herself into a serious-minded literary titan, while Eve Babitz’s novels and essay collections, compiled from the same social scenes but shaped more loosely and with greater spirit, fell into relative obscurity. That is, until Anolik tracked Babitz down in 2012, by then seriously ill and living in squalor. Anolik became obsessed, helping to restore Babitz’s reputation as a writer and chronicler of Los Angeles life, eventually writing the 2019 biography Hollywood’s Eve. “My preoccupation was unbalanced, fetishistic,” she admits here.

This time, Anolik uses Didion as the headliner, though seemingly through gritted teeth. When Babitz died, aged 78, in 2021 – just days before Didion, who was 87 – her sister Mirandi discovered boxes of papers in the back of a wardrobe. Anolik was reeled in by an excoriating but unsent letter from Babitz to Didion, which she chooses to interpret as a platonic “lovers’ quarrel”. Babitz assails her friend and occasional collaborator (Didion briefly edited Babitz’s first collection, before Babitz “fired” her) for what she perceives as Didion’s dislike of women, her contempt for art, and her deference to her husband. Anolik takes this wounded screed and runs with it, replaying Babitz’s story through its entanglements with Didion’s. This is vivid, entertaining stuff and often gallops along as if it’s been up all night at one of Didion and Dunne’s notorious Franklin Avenue gatherings, but it is, perhaps, more provocative than entirely convincing.

Rebecca Nicholson

Essays

Portrait of the artists

The Position of Spoons

Deborah Levy

The Position of Spoons Deborah Levy

Portrait of the artists

“It is a writing adventure to go in deep, then deeper, and then to play with surface so that we become experts at surface and depth,” writes Deborah Levy, and it’s as good a statement of intent as any in this collection, which delves into topics both trivial and profound: brothel creepers, car crashes, lemon curd, trauma.

The theme, insofar as there is one, is the artists who have inspired her. Many of these are women, and Levy writes skilfully on the complex interplay of self-presentation and effacement that’s often demanded of female creativity. Lee Miller “both hides from and gives herself to the camera”; Francesca Woodman makes “herself present by making herself absent”. Artists and writers invent things, but they invent themselves too.

Levy is good on the prices we find ourselves paying: for art, for love, for fitting in. Of Ann Quin, the avant garde, working-class writer who drowned herself in the sea off Brighton, she says: “I want to know more about what it took to want to swim home and I know Quin could have told me.” In another short piece called Values and Standards, she writes about an acquaintance she sometimes meets at the school gates. This woman’s husband takes pleasure in humiliating her; to survive, “she had removed her own eyes and saw the world and herself through his eyes”. Levy wonders if she ever “puts her own eyes back in”, and considers her own narrowing of vision at times when “other things had become bigger. Perhaps overwhelming.”

Here is Levy on the French writer and film-maker Marguerite Duras: “She thinks as deeply as it is possible to think without dying of pain … She puts everything in to language. The more she puts in, the fewer words she uses.” At her best, Levy pulls off a similar feat, plunging into the depths, taking us with her.

Freya Berry

Poetry

A dazzling voice

Bad Diaspora Poems

Momtaza Mehri

Bad Diaspora Poems Momtaza Mehri

A dazzling voice

The long-awaited debut collection from the former Young People’s Poet Laureate for London invites readers to consider the concept of diaspora. Mehri brings unflinching discursive skills to verse that melds criticism, autobiography and essay while still achieving a crisp sonic momentum characteristic of lyric poetry.

The meanings of diaspora in this collection are as varied as the forms Mehri deploys: prose poems, found poems, poems using emojis and erasures. “Diaspora is witnessing a murder without getting blood on your shirt.” “I don’t want to guard something I don’t own.” Mehri finds a new tone somewhere between Gwendolyn Brooks’s effortless musicality and Carolyn Forché’s noun-laced haunting intensity. Hers is a dazzling voice that refuses to speak from a podium, preferring to examine guilt, culture and personhood from within the “nightly decision” of community.

Oluwaseun Olayiwola

Fiction

Life after the apocalypse

Juice

Tim Winton

Juice Tim Winton

Life after the apocalypse

Tim Winton and speculative fiction may seem an odd combination. His novels excel at the here and now, depicting lives at the margins, young love and young parenthood, violence at the hands of fathers. But the harsh beauty of the western Australian landscape has long been a presence in his work, and Winton has also long highlighted his country’s fragility in the face of climate chaos, and been fiercely critical of the exploitation of Australia’s mineral wealth. So the cli-fi premise of Juice, his latest novel, could be a perfect Winton fit.

Set in an unspecified future, some centuries from now, the book opens on a man and a girl driving across a landscape blackened by ashes. The hellscape is worthy of the Mad Max franchise, with slave colonies springing up from the parched earth like termite mounds. There are echoes of Cormac McCarthy’s The Road here, too, in the black dust thrown up by the vehicle’s tyres, and in the child passenger, observing everything with a mute wariness. And Winton’s ending is a masterstroke, the heart-in-your-mouth final chapter one of the best things I’ve read in a long time.

Rachel Seiffert

Fiction

A historic hero

Yorùbá Boy Running

Biyi Bándélé

Yorùbá Boy Running Biyi Bándélé

A historic hero

Like the protagonist of Yorùbá Boy Running, Biyi Bándélé had been running from a young age. At 14, he won a writing competition at school; another award in his 20s, for his radio play script Rain, took him to London in 1990. He hit the ground running there, publishing his first novel, The Man Who Came in from the Back of Beyond, in 1991. This was the beginning of a prolific and multifaceted career that, sadly, came to an end when Bándélé died suddenly in 2022 at the age of 54.

At the time he was putting the finishing touches to his film adaptation of Wole Soyinka’s play Death and the King’s Horseman – a play very much centred on death and redemption and now available on Netflix as Elesin Oba: The King’s Horseman. He was also working on this posthumous novel, Yorùbá Boy Running, partly inspired by the history of Bándélé’s great-grandfather, who, like his protagonist, Samuel Ajayi Crowther, was formerly enslaved.

One doesn’t come to a posthumous novel for its perfect finish; not all the sections of the book are as polished or as inventive as the opening part. The editors have done a great job of ordering and signposting the different sections with dates and thematic headings, making it easier to follow the sometimes intricate chronology of the narrative. We are lucky and grateful that the author was able to leave us with this bookend to his glorious if truncated career that began long ago in Kafanchan, Nigeria, when he started running towards a distinguished future in faraway London.

Helon Habila

Environment

A message of hope

Into the Clear Blue Sky

Rob Jackson

Into the Clear Blue Sky Rob Jackson

A message of hope

Rob Jackson has a dream: to restore the Earth’s atmosphere to pre-industrial levels of greenhouse gases. For more than a decade, the professor of environmental sciences and chair of the Global Carbon Project has focused his research on reducing levels of methane, the greenhouse gas responsible for about a third of recent atmospheric heating. Methane concentrations are accelerating faster today than at any time. The cause is unclear but, as the climate heats up, it may may be due to emissions from tropical wetlands or thawing Arctic permafrost.

There is so much carbon dioxide in the atmosphere from fossil fuels that restoring its level to what it was before the industrial revolution is impossible. You would have to remove a trillion tons of pollution: “No one reading this book will live long enough to see that happen.” But that is not the case for methane, a far more potent greenhouse gas. Methane’s concentration could be restored to pre-industrial levels by removing “only” two to three billion tons: “My dream is to see this happen in my lifetime.” Jackson believes this is now the only way of slowing global warming in the next decade or two, in order to delay crossing critical temperature thresholds, such as 1.5 and 2C increases.

Jackson explains here the possible methods of “drawdown”, or cleansing greenhouse gases from the atmosphere. Extracting 400bn tons of carbon dioxide would cost $40tn, “larger than the combined annual GDPs of China and the US”. He frankly admits that removing methane from the air is more difficult than carbon dioxide. But the advantage is that, unlike carbon dioxide, it doesn’t need to be captured and stored underground.

Jackson points out the sobering fact that “no fossil fuel shows a sustained decline in global use”. Ultimately, this pollution will need to be removed if the Earth is to remain habitable. In this important book, Jackson makes a compelling case for methane removal, together with emissions reductions. He lucidly explains the threats facing the planet, as well as the science of drawdown. Through conversations with innovators, conservationists, business leaders and activists, he offers a powerful message of hope, showing how change can and must happen, if we are to restore the climate and reduce global temperatures.

PD Smith