April 24, 2025, 3:48pm

This political moment in America has been chilling for free speech and dissent, but like so many things about America, this government and vigilante repression isn’t new. Before Mahmoud Khalil, Rümeysa Öztürk, and Mohsen Mahdawi speaking out against war and genocide, there were Art Young, Max Eastman, and The Masses speaking out against war and conscription.

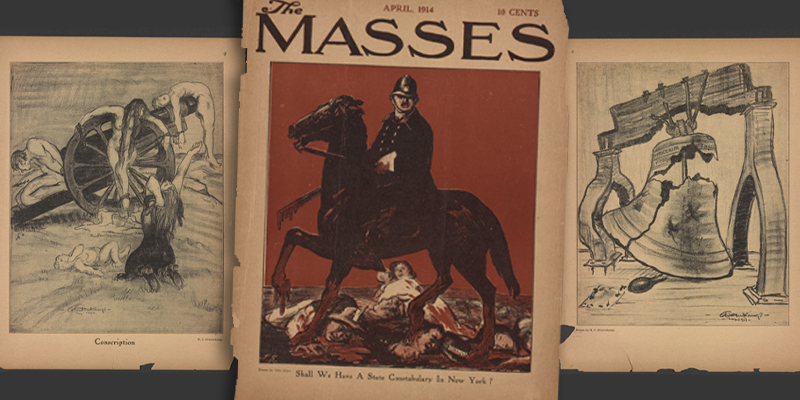

The Masses was a literary magazine that ran from 1911-1917, and published a wide variety of writing: fiction, poetry, reporting, art and essays by Walter Lippmann, Sherwood Anderson, Edna St. Vincent Millay, John Reed, and more. Founded by a Dutch socialist immigrant, the magazine was also richly illustrated, which is probably how it’s best remembered today. The Masses championed both modernist and realist illustrations, and ran political cartoons by Art Young and Fighting Bob Minor, among others. Take a scroll through their covers — their style grew and evolved into something very contemporary over the years.

I haven’t read the full run, but by all accounts The Masses was staunchly left-leaning and socialist, but it wasn’t seen as dogmatic either. The magazine’s most prominent editor, Max Eastman, wanted to make a magazine that championed radical ideas as well as art for its own sake. He envisioned “A Free Magazine”:

This magazine is owned and published cooperatively by its editors. It has no dividends to pay, and nobody is trying to make money out of it. A revolutionary and not a reform magazine; a magazine with a sense of humour and no respect for the respectable; frank; arrogant; impertinent; searching for true causes; a magazine directed against rigidity and dogma wherever it is found; printing what is too naked or true for a money-making press; a magazine whose final policy is to do as it pleases and conciliate nobody, not even its readers — There is a field for this publication in America. Help us to find it.

Eastman had joined the magazine with a group of contributors from NYC’s Greenwich Village, a creative and activist group of bohemians who created the Greenwich Village reputation that still remains today. In August 1912, this group elected/forced Eastman to be The Masses’ editor. He learned of his new job from a short note: “You are elected editor of The Masses. No pay.”

Politically, The Masses covered and championed the causes of working people and was aligned with many of the reformist and revolutionary causes of the Progressive Era. They were broadly pro-labor, pro-women’s suffrage, pro-birth control, and pro-social. They were staunchly on the side of the worker and the striker, which led them to their first run-in with the law.

In 1912, The Masses accused the Associated Press of covering the Paint Creek-Cabin Creek mine workers strike in a way that favored the employers and their hired private detectives. The A.P. brought suit, and Eastman and the cartoonist Art Young were arrested by New York City’s DA on charges of libel against the A.P. and its president. But after two years and a lot of litigation, the case was quietly dropped.

But the magazine’s real problems came after America entered the First World War. President Woodrow Wilson, who championed America’s march into WWI, was worried by the number of Senators and members of Congress who had voted against the Declaration of War. Seeking tools to curb dissent, the President pushed the passage of the Espionage Act, which gave the government vast power to squash speech they didn’t like.

Fears that anti-war sentiment and the spirit and politics of the 1917 Russian Revolution would spread in the U.S. led to swift implementation of the Act. As historian Adam Hochschild said in The Nation’s “Start Making Sense” podcast: “They did lock people up under the Espionage Act and under copycat legislation, which many states passed, and even some localities… Between 1917 and 1921, roughly a thousand Americans spent a year or more in jail.”

The law made illegal any interference with the military’s operations and its recruitment efforts. This is the legislation that led to socialist politician Eugene Debs’ arrest and sentencing to a ten-year prison term after he gave an anti-war speech in Ohio. Debs was still in Atlanta Federal Penitentiary two years after the war ended, when he ran for president and won nearly a million votes.

The Wilson Administration also used the Espionage Act to deputize American vigilantes to target dissent. The Justice Department created the American Protective League, an officially sanctioned vigilante group that beat up attendees of anti-war rallies, targeted draft dodgers, and organized raids to arrest anyone caught without their draft exception papers. By the end of 1917, a quarter of a million Americans were wearing the official League badges.

Most crucially for publications, the Espionage Act also allowed the Postmaster General, Albert Burleson, to “declare a publication unmailed.” Around 75 publications were targeted this way and could no longer be mailed, including The Masses. The Post Office went after their August 1917 issue, and cited a number of illustrations and articles as “treasonous,” including a cartoon of a cracked Liberty Bell and another of corpses lashed to a cannon titled “Conscription.” The magazine tried to challenge their ban, but the government escalated, not only specifying the work they felt was anti-military, but also adding additional charges against contributors.

Unable to ship copies to subscribers, the magazine folded three issues later, though some of the staff quickly started a new magazine, The Liberator, taking the name of Lloyd Garrison’s abolitionist paper.

A month after The Liberator was founded, The Masses and its staff went on trial in New York for “obstruct[ing] the recruiting and enlistment” of the military. None of the accused took their charges or the trial very seriously, seeking to undermine the case’s credibility with disruptive humor:

Contributing to a carnival atmosphere that first day of the trial was a band just outside the courtroom window patriotic tunes in a campaign to sell Liberty Bonds and disturbing the solemnity within the courtroom itself. Each time the band played the “Star Spangled Banner” [The Masses’ business manager] Merrill Rogers jumped to the floor to salute the flag. Only after the fourth time that the band played the tune and only after the Judge asked him did Rogers finally dispense with the salute.

Despite the ruckus, Second District Court Judge Learned Hand seemed to sympathize with the defendants and dismissed some of the charges. The case ended in a mistrial and in violence: one juror was a socialist, and would not agree to the majority opinion, thwarting a unanimous decision. But the rest of the jurors were livid at the one outlying juror, and asked the court to charge him, before they attempted to force him outside and lynch him. Thankfully they were stopped.

A few months later, The Masses was dragged back in front of a judge, but this case also ended in a mistrial. But by then, the magazine had been dead for nearly a year, so the exoneration was bittersweet.

The Espionage Act, on the other hand, marched on. Postmaster General Burleson kept banning publications for another three years, until the very end of Wilson’s term, even after the President told him explicitly to stop after the war ended.

The vigilante American Protective League survived too. The Justice Department formally disbanded the League after the armistice, but many of the groups simply renamed themselves and kept intimidating and beating up left wing dissenters.

Presidents Harding and Coolidge released everyone who was convicted during the war under the Espionage Act, and some of its amendments were repealed. But the Act has remained on the books, and was the law behind the charges of Emma Goldman, Alexander Berkman, Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, Daniel Ellsberg, Chelsea Manning, Julian Assange, and Edward Snowden, to name a few.

It’s as trite as it is true, but there are always rhymes in American history. 2025 isn’t the first time our neighbors have delighted in violence against a minority, it’s not the first time censors have told us what we can and cannot read, and it’s not the first time the government has enabled our worst and ugliest impulses. It’s up to us, with solidarity and courage, to make sure it will be the last time.