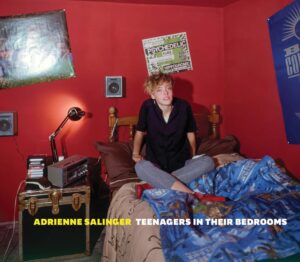

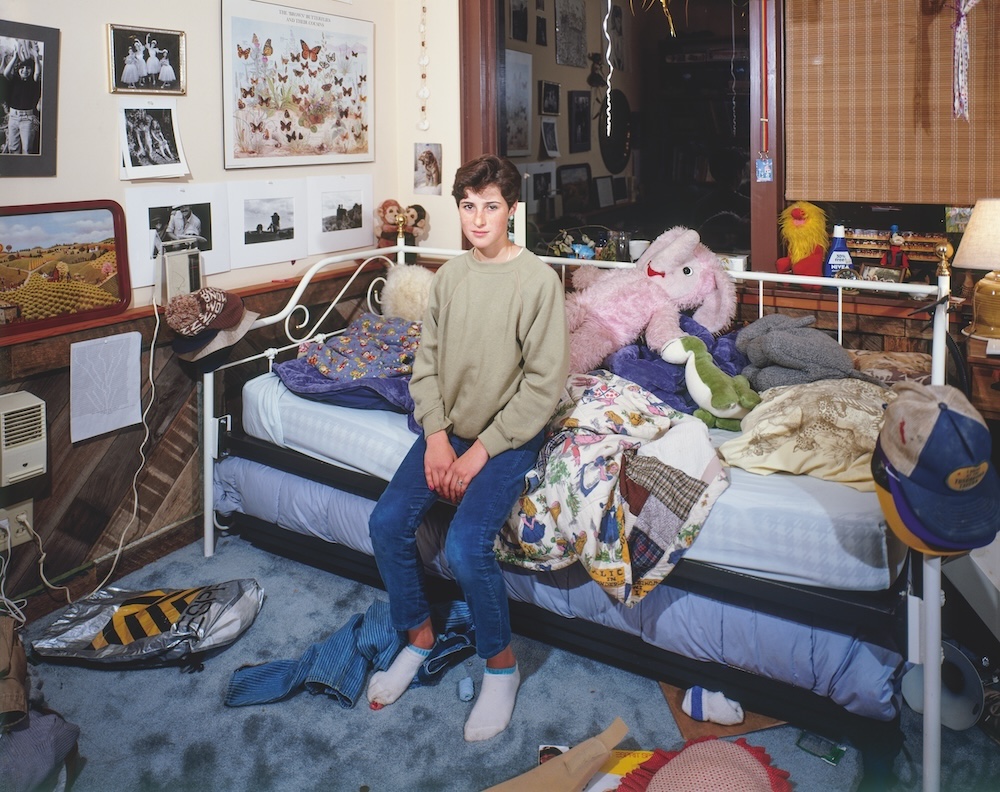

The idea behind most pictures is to capture the present as it becomes the past. Not the pictures in Teenagers in Their Bedrooms. What Adrienne Salinger has given us are images of the present as it becomes the future. She’s caught these emerging citizens, these teenagers in their bedrooms, just as they’re about to enter the fullness of their lives. The future waits outside every frame.

It seems to be what they’re looking at so uncertainly, or defiantly, or stoically. If so, the future is a kind of mirror, because they are it. They’re our future, anyway. In days to come they will take our jobs, marry our sons and daughters, operate on us, defend us from our enemies foreign and domestic, vote us out of office, take away our cars, decide what our allowance should be, acquaint us with our failures, forgive us, maybe, and bury us. So it’s impossible not to take an interest in them.

They can be tough to get to know. That’s one of the painful duties of a teenager, to be tough to know. But I had the feeling as I studied their pictures and read their words that they had allowed Adrienne Salinger to know them very well indeed. The setting of these pictures—their bedrooms—implies a condition of the most extraordinary trust. Any grown-up who has recklessly entered the bedroom of a teenager without knocking knows what it means to receive a cool welcome. And why not? We hold the title to everything else—why shouldn’t they defend the borders of their own small claim from the Other? But there’s no atmosphere of invasion here, no sign of affronted privacy. Quite the opposite. You can sense in their faces and their words a rare confidence in that Other to whom they have opened their doors.

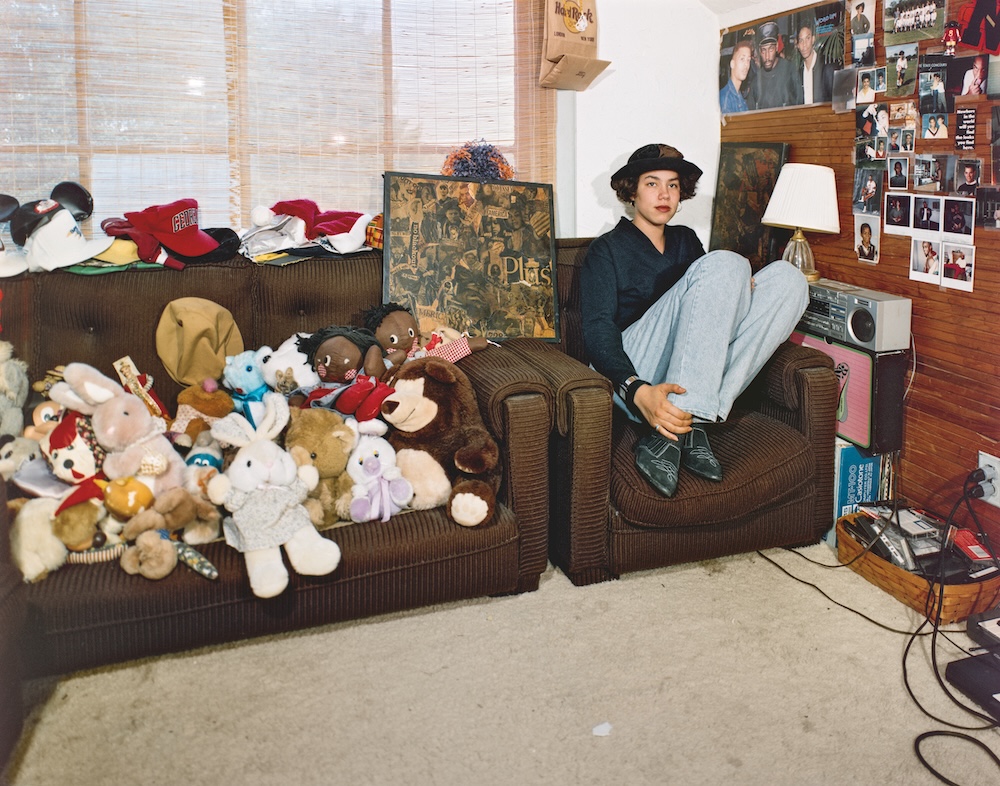

This confidence was not misplaced. A camera is often an unfriendly witness because of the ease with which photographers can make their subjects appear shallow, coarse, or vain while excusing themselves from any imputation of malice by appealing to the objectivity of the lens. But a photograph is not objective. It is composed, and the intentions of the composer have everything to do with the outcome. Under another eye, these teenagers could have been reduced to cartoons. The props are all there, the T-shirts, the hair, the tattoos, the sunglasses, the fingerless gloves, the AC/DC and Megadeth posters, MTV.

The humanity of these young faces implies a depth of feeling and experience that their histories confirm.

If Adrienne Salinger had wanted to present her subjects as satiric clichés, she could have. But “subjects” is too cold a word for the way she views them, with such evident affection for their singularity, the difference each of them brings to the world. Rather than framing them in conventional perceptions, she allows them to present themselves, not only in the poses they assume but also in the words they choose to tell about their lives. Each encounter becomes a dramatic monologue.

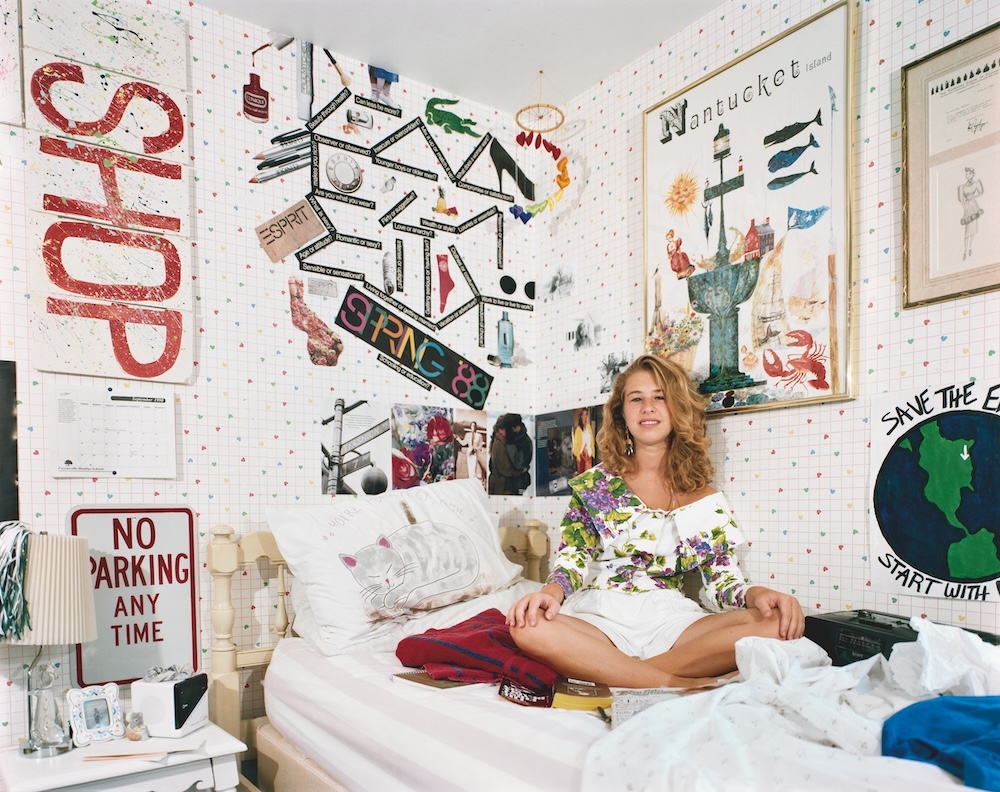

The result is unfailingly dramatic and powerful. Not since Let Us Now Praise Famous Men have I come across such a rich collaboration of image and story, each compelling in its own right and often overwhelming in combination. The humanity of these young faces implies a depth of feeling and experience that their histories confirm. Dena D. came home the day before she started her freshman year in high school and discovered that her mother had killed herself. Things did not go well for her afterward. “When I started school, none of my friends would talk to me. They were scared. Nothing bad had ever happened to them. I started hanging out with people who smoked and did drugs. They accepted me no matter what. . . . After that, school wasn’t really that important.”

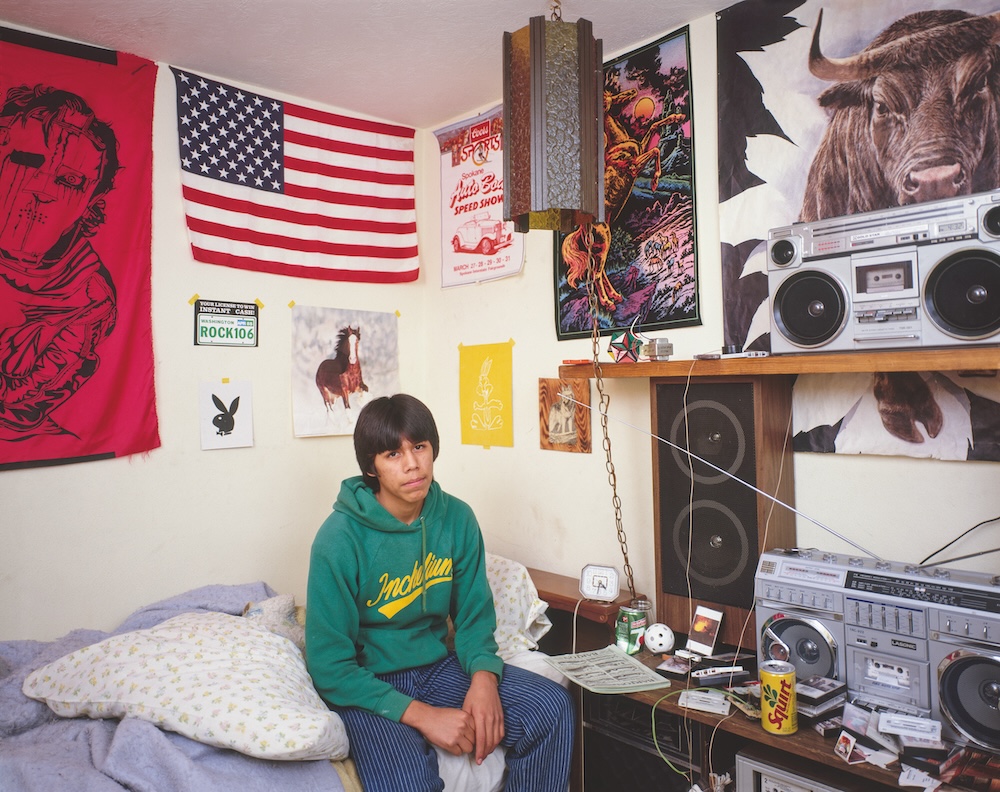

Carlos C.’s father, a hemophiliac, contracted AIDS through a transfusion. No one told Carlos his father was dying or what he was dying of. His mother had left sometime earlier. Now he makes his home with “Uncle Bill,” a friend of his father’s, a gay man whom he has grown to admire and love as if he were a real uncle. Carlos is without bitterness at the sudden turns his life has taken, but not without wonder. He can’t help remembering the days when he had “a normal family—mother, father, dog, sister, cat.”

Carlos is not eccentric in his capacity for spiritual endurance. Considering what they’ve been through—drug addiction, adoption, racism, nervous collapse, pregnancy, abrupt dislocation, alcoholism, desertion, and physical abuse on top of all the usual pressures and hurts of growing up—the teenagers in these pictures face the world with a striking absence of cynicism and self-pity. More often than not, their own troubles wake them up to the troubles of others “I didn’t know I’d be spending thirty days of my life in a hospital,” Danielle D. says of her breakdown. Then she adds, “Some kids there didn’t have parents and just came in off the streets, and they liked it because it was safer than jail.” And they can be droll about their encounters with adult logic. Jennifer G. got suspended for cutting classes and going to the mall. “They kicked me out of school for three days. And I said if you think you’re punishing me, you’re wrong. You’re giving me the coolest thing you could give me. Three days out of school for free. You’re kicking me out of school because I skip. That doesn’t make any sense.”

There are no grown-ups in these pictures. You can feel them just outside, though, mostly well-meaning but anxious and confused, some to the point of brutality, others to the point of immobility. When Auto C. was nine years old, his father hit him with a hatchet for getting in the way; when Alex V. spent a night away from home without telling her mother and father, they did nothing. “I wish my parents were a little more straight,” she says. But as if they can foresee the mistakes they’re someday going to make, the same ones we’re making now, these teenagers are longer on understanding than blame. Of the father who hit him, Auto C. says, “He was abused when he was a kid. . . . I was the oldest and his namesake, and he wanted me to be his showpiece, so when I fell short of his expectations, he’d snap.” But Auto doesn’t pretend that this insight comes free of cost: “I don’t get attached to people very easily.”

You can’t help but take an interest in such people and the way they navigate these hard years. Some are inevitably adrift and at hazard. For others the course comes easier, but for none of them does it come easy. One of the many pleasures of this book is to recall your own passage, and to think how lucky you were to have made it in decent enough shape to be reading this or any book. Another is to acquaint yourself with the courage and good-heartedness of those who are making it now, and who will one day lead us out to pasture. But the greatest pleasure of all is the experience of Adrienne Salinger’s brilliant, generous artistry, with its perfect instinct for the essential word and expression, the moment in which the hidden person is revealed. She does not impose herself on a single frame or sentence of this work, but its kind and witty atmosphere, and the tender effect of the whole are entirely her own. Teenagers in Their Bedrooms is destined to be a classic, as certain to endure as the young spirits that it celebrates.

–Tobias Wolff, 1995

*

All photos below from are from Adrienne Salinger: Teenagers in Their Bedrooms, courtesy the artist and D.A.P.

*

*

*

*

*

___________________________________

From Adrienne Salinger: Teenagers in Their Bedrooms. Introduction by Tobias Wolff, courtesy Adrienne Salinger and D.A.P.