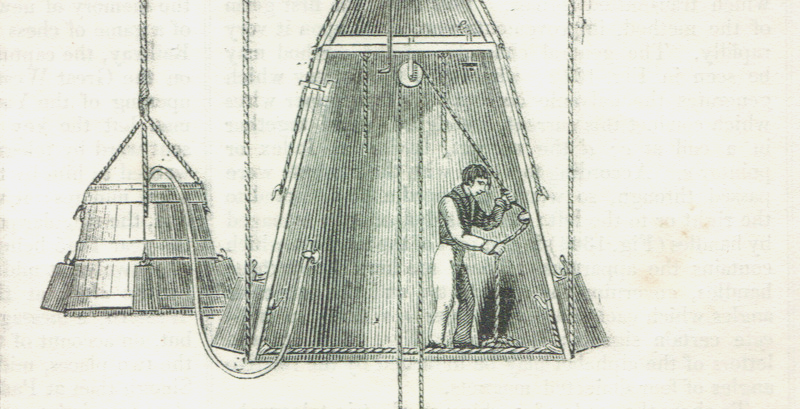

Before the submarine, there was the diving bell, and before the diving bell, there was the ephemeral but persistent human dream of sinking, the nagging drive to embed the body into a balloon-like enclosure and float alongside the fishes. To see as they see. The diving bell—a rigid, airtight capsule lowered to depth and raised by a winch-driven cable from a support platform at the surface—was first chronicled in the fourth century BC by Aristotle, who wrote, “They enable the divers to respire equally well by letting down a cauldron, for this does not fill with water, but retains the air, for it is forced straight down into the water.” Aristotle, who is often cited as the “father of marine biology and biodiversity,” spent at least five years of his life on the coast of Asia Minor, and there he may have used the diving bell to observe and first classify and name our sea creatures.

Article continues after advertisement

At depth, he became the first to distinguish between the “blooded” and the “bloodless” animals; the “soft-bodied” creatures (octopi and squid), the “soft-shelled” creatures (lobsters, shrimp, hermit crabs), and the “shell-skinned” creatures (bivalves, gastropods, sea urchins, sea stars). He began a list of miscellaneous creatures—singular beasts he couldn’t shoehorn into one classification: sea cucumbers and anemones, isopods and jellyfish.

Aristotle was able to see his obsessions from a scholarly remove, and to recognize that his drive to spend so much time at depth may have begotten a sort of madness.

Aristotle grew obsessed with mapping the goings-on of the watery world. It seems he was addicted to the ornaments of the deep sea and incorporated his observations of the movements of transparent jellyfish, for instance, into his thoughts on the nature of memory and the soul. He wrote that dreams were akin to waking life “moving in a wavelike motion, as in a body of water.”

Aristotle was able to see his obsessions from a scholarly remove, and to recognize that his drive to spend so much time at depth may have begotten a sort of madness (“No great mind has ever existed without a touch of madness,” he snarkily wrote). Of course, Aristotle would have been aware of the treatise on “madness” written by Hippocrates, titled On the Sacred Disease, in which the ancient Greek physician described insanity as a “wet disease…ascribed to a wet condition of the brain involving excess movement.”

Aristotle believed that people—men, specifically—who were excluded from positions of power and civic influence, or men who had recently endured disappointment or failure, often tend to remedy that failure first via a brief period of self-isolation (in, for instance, a workshop or a laboratory or a diving bell), and then by resorting to violence. He further mapped this social philosophy onto his opinions of stage drama. Any tragedy worth its salt, he believed, if it was to bear any resemblance to the actual human condition, must incorporate acts of violence: “the broken and dismembered bodies” of well-drawn tragic characters must “occasionally [be] brought onstage.”

*

In 343 BC, Aristotle was hired as a tutor to thirteen-year-old Alexander the Great, to whom he passed on his obsession with the diving bell. Legend has it that Alexander commissioned the construction of his own bell, which he affectionately named Colimpha, or “Swimmer.” In numerous medieval-era images of Alexander, he appears ensconced in a submersible, floating among fantastical creatures. In European, Arabic, and Persian adaptations of the Alexander Romance (a text on Alexander’s life, fusing history, biography, myth, and legend-making originally drafted sometime before AD 338), the conqueror is likewise shown suspended in a capsule beneath the sea.

According to this bumping-and-grinding of history and legend, Alexander used his diving bell not only as a tool by which to explore and subsequently dominate much of the Mediterranean but also as a quiet retreat, an isolated space in which to meditate on the blood he had shed on his journey toward “greatness,” and the blood he still had to shed in order to maintain and expand it. Thanks to the atmospheric influence of his diving bell, Alexander was able to conjure a sense of blissful calm, even as he was cutting someone’s throat.

In 332 BC, when he was only twenty-four years old, Alexander besieged the city of Tyre by first assessing its harbor underwater in his diving bell. He then instructed a portion of his army to remove the obstacles he found there, allowing his troops to arrive by sea unimpeded. Emerging from his submersible, he and his army defeated the Tyrian army and overtook the city, where Alexander subsequently directed the torture and massacre of over eight thousand unarmed Tyrian civilians and the enslavement of another thirty thousand women and children. As he boarded Colimpha, triumphant, he ordered the crucifixion of another two thousand residents, right there on the beach. Legend has it he watched these executions with a serene expression, and finally closed the hatch of his diving bell and set sail only after the last of the captured had gone slack on the cross.

By the age of thirty in 326 BC, Alexander used this meditative murderousness to amass his empire, which included much of Africa and India. When he died two and a half years later on June 10, 323 BC (purportedly due to assassination by poisoning), his body was placed in a golden anthropoid sarcophagus, which was filled with honey. In this way, his body never actually touched the solid frame of the casket, but was allowed to float “happy and unvanquishable forever” (according to the seer Aristander) in the sweet thickness, a vessel itself, an arrested submersible.

*

According to the neuroscientist Dr. Ali Venosa, “the human body is either one of the most vulnerable things on the planet, or one of the most resilient. It’s true we can do amazing things—heal where we once were bleeding, attack and destroy unfriendly microbial invaders, even knit our own bones back together.

“But what exactly can we take?” Venosa is compelled to ask. “What are the limits of our survival, and what happens to our body if we cross them?”

At depth, the lungs contract, and the brain and heart can grow saturated with blood, unnaturally powered to the point of exhaustion, which can result in a pressure-borne vertigo-cum-euphoria, the sense of existing outside of time and space, but still ensconced in and “mothered” by diving suit or submersible.

But if one goes too far when scuba diving, or is aboard a submersible that fails at depth, one can die from bleeding into the lungs, as the organs, according to the Centers for Disease Control, “exceed the elastic limit of the lung tissue.” Many things can go wrong, in fact; a scuba diver or submariner attempting an escape from a malfunctioning sub can be knocked out by the pressure, or have a seizure, or succumb to nitrogen narcosis or oxygen toxicity, or drown.

According to the biologist Dr. Neosha S. Kashef, if one is fortunate enough to resurface from such depths, the person “will appear inflated…eyes bulging out of [their] sockets…as if blown up like a balloon.”

Though the hull of a submersible can protect us from the more extreme effects, submariners remain at risk. “If a person in a deeply submerged submarine rapidly surfaces without exhaling during the ascent, sudden expansion of air trapped within the thorax can burst one or both lungs,” stresses Dr. Michael F. Beers, professor of medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. Of course, said effects manifest at depth during submersible malfunctions as well.

The men who manned the submersibles of old were not always the best of influences. But to their less scientific contemporaries, they were mermen, gods.

At depth, in the human body, the nitrogen in the air we breathe diffuses into our blood and tissues in a higher concentration than on land. When we surface, this nitrogen can form microbubbles in our blood and our tissues, resulting in decompression sickness. In short, our insides effervesce, pop and fizz as if carbonated. People often experience this trauma as a cocktail of emotional ecstasy and physical pain. Rhapsody jockeys with agony, beatitude with torment. “Behavioral and cognitive aspects of cerebral decompression sickness may be persistent or slow to improve,” writes the neurologist Dr. Herbert B. Newton. The sickness “manifests as an alteration of mentation.”

Frenzy can ensue—woe, intoxication, ravishment, madness—the sort that can compel a person to laugh or howl in ways that may seem inappropriate or eccentric; to exhibit wild behavioral outbursts before crashing, exhausted; to experience life—actually and metaphorically, physically and emotionally—in rapidly alternating periods of decompression and recompression. It’s the compression that’s the common denominator. Can we ever fully recover the equilibrium we once had inside us before we indulged in our compulsion to sink?

*

Imagine Aristotle bobbing amid the ancient depths, fogging up the glass of his diving bell, watching a sea monk agitate the water. Imagine Alexander, a few years later, doing the same. What happens when ancient instances of madness sour—if only narratively—into genius? The men who manned the submersibles of old were not always the best of influences. But to their less scientific contemporaries, they were mermen, gods, larger than the life that imprisoned the mouth breathers on the surface.

And like our best gods, they were mad, and they were bloodthirsty, and they were celebrated, and they begat future men who confused greatness with meanness, and who used their advanced tools to make better bells. And these men sailed and bobbed like Aristotle and Alexander before them, and fogged up new glass, and spotted new creatures, and used their machines to arouse the curiosity of their contemporaries on whose bodies they took out their frustrations, and became, too, names uttered from so many lips—whispers, screams, totems of disgust and caution and malign curiosity. Once again, celebrity and murder found themselves conjoined, as the ocean floor seethed with metal and flesh, and down there, not a single sea monk opened its eyes. Because we now tell ourselves we know better; sea monks don’t exist. But people do. For better or for worse, people do.

__________________________________

Excerpted from Submersed: Wonder, Obsession, and Murder in the World of Amateur Submarines by Matthew Gavin Frank. Reprinted by permission of Pantheon Books, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2025 by Matthew Gavin Frank.