In White Sands, New Mexico, she hikes up the dunes with her family. The sand is made of gypsum, which, unlike other desert sands, is cool to the touch. The dunes seem to trace the contours of an endless body. They exist because 280 million years ago in the Permian, this area was covered with a shallow sea.

Article continues after advertisement

Agnès Varda tells us: “If we opened people up, we’d find landscapes. If we opened me up, we’d find beaches.” When she crouches in the dunes and sifts the silky gypsum crystals through her fingers, she thinks: if they opened me up, they’d find the Permian Sea.

That the body can be a landscape; that the body can be tied to earlier histories.

No, not just can—is.

*

In natural history museums, the Permian Sea dioramas are her favorite. Rugose corals, nautiloids, and brachiopods—“lamp shells,” since their shapes resemble little clay oil lamps. It floods her body with warmth to think of it: shallow seas would be full of sunlight after all.

If all life living now has a common ancestor, if her body has DNA in common with seahorses, lemurs, honeybees, those bodies aren’t just other “animals.” They’re her siblings.

Gypsum is not sand—it’s a mineral that can dissolve in water. In crystal form, it’s actually clear. But the wind tumbles and rasps those surfaces, scratches them opaque. Not sea-foam white or cloud white. A kind of otherworldly brightness. The kind of whiteness against which ghosts might appear.

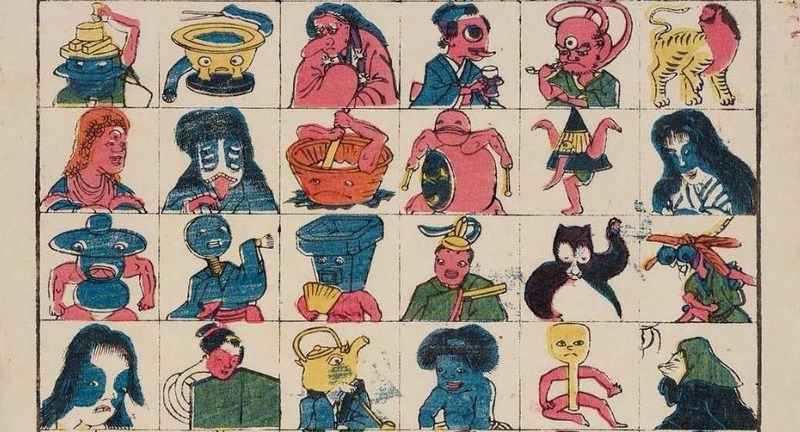

Later that trip, they visit the Museum of International Folk Art in Santa Fe, where she finds an exhibit on yōkai: the “ghosts and demons of Japan.” Shape-shifters, specters, and supernatural beings described as both “ghastly and comical.” There is an 18th-century parade-of-monsters scroll, a fairy-tale book titled “The Tongue-Cut Sparrow.” There’s an unnerving video installation of the wooden head of a smiling geisha that splits open to reveal horns and a massive set of pointed teeth.

Once home, she checks out every library book on yōkai she can find, even the graphic novels. Learns about amikiri—a lobster-shaped yōkai with enormous scissors instead of hands that likes to snip mosquito nets. A hajikkaki—a blobby, pale creature so shy it lives underground (and if you dig it up, will curse you with something shameful or embarrassing). Monster cats, women with ravenous mouths in the back of their heads, mountain goblins, mermaids with carp bodies, foxes that transform into samurai messengers—the list goes on.

But her favorite by far are the haunted household objects: tsukumogami.

*

She sometimes imagines that these places she is trying to tell you about are only accessible from dark rooms with sets of complicated staircases. You can never see the room you are trying to get to; you can only see, step by step, the stairs you need to take to arrive. In her mind, these staircases are lit by grainy spotlights—monochromatic, diffuse. In her mind, these staircases are full of sand.

*

Tsukumogami translates to “ninety-nine spirit”—referencing the idea that any object, upon reaching ninety-nine years of age, could become animate. As authors Hiroko Yoda and Matt Alt explain: “The roots of tsukumogami are found in the animistic tradition of Japan’s native religion of Shinto, which holds that not only human beings but all things, living or inanimate, can be repositories for souls.”

The 16th-century scroll Tsukumogami Emaki (Illustrated Scroll of Animals) is a brief tale about a collection of used household objects (a tea kettle, a bamboo shamoji or rice spoon, an old kimono, etc.) that have turned into yōkai. As Saitō Maori tells us, “Sometime in the Kōhō era (964–968), during the year’s spring cleaning, a number of old utensils are ungratefully discarded. Because of their intense sense of indignation at being cast away, these disgruntled utensils become animated, bent on getting revenge on their human owners.” The utensils party and rabble-rouse and cause a ruckus. And eventually, end up at the Tō-ji Temple and become enlightened.

There are hundreds of tales in this “Muromachi” genre. Many are accompanied by exquisite illustrations. Her favorite drawing in the Tsukumogami Emaki is the one-eyed rice spoon (shamoji). But she also loves the four-legged tea kettle, and the prayer bead string with its little faces.

Tsukumogami can be haunted teapots turned into tanuki— Japanese raccoon dogs. Shoji screens that fill with watchful eyes. Or paper lanterns with faces, ancient mirrors that gain sentience. There’s even a grater that transforms into a porcupine.

With small children, the domestic becomes a sphere that is all-encompassing. Dishes. Bottles. Spoons. The tsukumogami interest her. It isn’t a stretch to imagine the walls have eyes. That the mirror is possessed, the bed has an attitude problem. “Artifact-spirits,” “haunted-relics,” “thing-wraiths.” At the museum, there was a giclée print of contemporary tsukumogami: a Kleenex box with legs, a couch with an open maw.

When she reads they are known to be furious if discarded after serving their human owners so faithfully, she laughs out loud. As a mother, this is something she can relate to.

*

When she says if they opened her up, they’d find the Permian Sea, she means it both metaphorically and literally. The end of the Permian was the world’s most extreme extinction event. Our bodies are here because our bodies moved through those bodies that survived it.

Consider: if all life living now has a common ancestor, if her body has DNA in common with seahorses, lemurs, honeybees, those bodies aren’t just other “animals.” They’re her siblings.

Ecofeminist Lisa Kemmerer tells us, “Through dualism, those living in patriarchies tend to view the world in terms of opposites, beginning with male and female, and extending to a plethora of other contrived divisions, such as white/other races, human/animal, culture/nature, and reason/emotion.”

Landscape/Body. Human/Nature. Human/Animal: false dichotomies. The idea that we must leave the human world to cross over to the natural world is a false dichotomy. The human/nature binary is a construct of humans.

We are the natural world. We are the world’s body. There is no separation.

*

Perhaps she can’t help thinking about the Permian Sea these days because we find ourselves again in a place of mass extinction.

Kemmerer again: “Most ecofeminists reject dichotomies and hierarchies as alien to the natural world—nature is interconnections.”

A writing friend tells her the math of this essay is loose. If a body is a landscape, can it also contain a landscape, he asks? What’s up with all the haunted objects? And where do all the staircases go?

She is aware that in this essay, things are spilling into other things. She knows the math is loose. That the staircases are now pouring sand. And yet.

This essay is feeling around in the dark for pieces that have been forgotten, pieces that are missing. This essay looks at Constantin Brâncuși’s Sleeping Muse and wonders where the rest of the body is, and why museums only ever build display cases for the disembodied heads. Maybe the muse’s body, invisible, is huge. And beautifully monstrous.

Maybe her body is everywhere. Perhaps that’s the reason this essay is trying to build a different kind of staircase.

*

Here’s what’s interesting to her about the tsukumogami. Reading about them begins to subtly change her. Washing a teacup. Cleaning a mirror. Drying a spoon. All of these things someday could be alive, she finds herself thinking. Perhaps they are living now.

That possibility: when one believes a thing is conscious, one treats it with tenderness. She knows this might sound strange. She admits it felt strange to see this happening to her too. Now, she finds herself doing things that she’s never done before. For example, in Marie Kondo’s infamous book on tidying, she suggests you hold an object and thank it for its service before letting it go. Here’s the difference: when, following Kondo’s directive, she thanks an object now, she imagines that it hears her.

Not adopting animism as a practice exactly. But rather, recognizing that the boundaries are blurry. That trying to continue to see things differently, to listen differently, is a practice too.

In her book, Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things, philosopher Jane Bennett asks us: What are the implications of considering everything as animated—including landfills, rocks, metals, and electricity? To think not in life/matter binaries, but rather to consider ourselves as participants in swarms of entangled, interconnected, jostling bodies that are constantly shifting, being modified and transformed? “For example,” Bennet asks, how “would patterns of consumption change if we faced not litter, rubbish, trash, or ‘the recycling,’ but an accumulating pile of lively and potentially dangerous matter?”

One could argue that the current environmental crisis is a crisis of vision and visioning—that is, the inability to imagine realities and trajectories other than the ones we are currently living. Also, the inability to envision what our current trajectory will end up looking like.

Which leads to this thought experiment:

Suppose there is a house, and in this house, the household objects are portals in which spirits can slip in. Let’s say there’s a woman that lives in this house, who, upon reading of the new extinctions—the Spix’s macaw, for example—begins to think she hears the cries of birds from the powdery turquoise of her coffee cups, the pottery bowl that holds her fruit.

Let’s say she ignores it for a while: the job of caretaking her two young children is both monotonous and immense. Anyone that sleep deprived is a little crazy.

The idea that we must leave the human world to cross over to the natural world is a false dichotomy. The human/nature binary is a construct of humans.

But let’s say the woman in that house begins to dream of another house. A much larger house, filled with other spirits. Now her children are a little older, and she starts to notice more inexplicably odd occurrences. Her shower curtain, for example. When it gets wet, it squeaks the “chaa-chaa, chaa-chaa” call of a lime-green Réunion parakeet.

Let’s say it becomes clear there are now staircases back and forth between these houses, and in her house, other spirits have started showing up in other objects—a trickle that quickly becomes a stream.

Suddenly, her teapot coos at her like a Mariana fruit dove. Her mirror, when she’s washing her face, flaps its reflective surface shut with a set of monarch butterfly wings. The clock on the dining room wall blinks at her with the amber eyes of a Seychelles scops owl. Her snow leopard lamp stretches its paws at dusk, then curls up, purring in moonlight.

Let’s say part of the reason this essay must come to life is because she’s afraid if nothing is done to stop these particular hauntings, they will spill out from these doors and into the houses of her children and their children too.

Let’s say she begins to write a book because she realizes that it never has just been about her house or her children.

This, too, is a false dichotomy.

*

Here’s her point: What if we had to live, remembering? Would we do something different if we knew we’d have to live alongside ghosts?

When one believes a thing is conscious, one treats it with tenderness. Perhaps even this essay is thrumming with the desire to be more than a boundaried object. Even this essay is learning to be alive.

Her daughter likes a subspecies of tsukumogami: the “teapot samurai.” It’s made entirely of discarded dinnerware: the head of a sake bottle, body of a teapot, skirt of a soup bowl (inverted), and arms and legs of whatever discarded utensils happen to be lying around. Unlike Humpty Dumpty, she’s warned, the seto-taishō can reassemble after a fall.

She likes this thought too. That lost and broken things don’t just reanimate but can continue to self-repair.

*

There were so many more staircases than she realized. Staircases not just to rooms but to other houses, other mothers. Staircases to so many other beings. Can you hear the sand now? It’s falling faster, sifting down with its swish, swish, swish.

If you can hear it, that’s because the staircases are not staircases at all, and the houses are not houses. There is no out that is not in. It is an invention, this being separate.

Her body is the Permian Sea. Your body is the old-growth forest of Fontainebleau. This soapy dish carries the spirit of a Ganges river dolphin.

__________________________________

From Wedding of the Foxes: Essays by Katherine Larson. Copyright © 2025. Available from Milkweed Editions.