“The Minotaur more than justifies the existence of the Labyrinth.”

–Jorge Luis Borges

*Article continues after advertisement

One of the most monstrous things I have ever seen was on a family holiday to Southern France when I was about twelve years old. After days spent swimming and playing fractious family tennis matches, we decided to experience some local culture. It was a short drive to see a bullfight in the nearby town of Arles. We filed into the wooden amphitheatre seats and felt the energy mount as the matadors strutted around the ring in their bright brocade tailoring. An announcer roused the crowd in Spanish.

Then the first fight began—a cage door opened and the bull skittered out across the sand. I had expected it to be far larger, for some reason. Its shoulder barely reached to the matador’s chest, slender legs finishing in neat, cloven hooves. Its horns looked lethal, though.

What followed was a game of cat and mouse, which the matador wanted to play and the bull didn’t so much. Every time the bull attempted to slope off to the side of the arena to mind its own business, the matador would pursue it with a flourish. The first spear was a shock, delivered ostentatiously to the nape of the bull’s neck, drawing applause from the audience. The blue and pink frills of the banderilla spear shaft bobbed up and down as the bull bucked in irritation and blood began to seep down its sides.

The bullfight is a struggle between man and his beastliness. It’s an eruption of violence, a pressure valve for the eternal problem of what to do with the animal inside.

After about ten minutes, the animal was pin-cushioned with lances and dripped a trail of blood in the sand. All I could think about was the pain of them twisting in its flesh as it moved. The matador, buoyed by the crowd’s cheering, pressed his pirouetting attack harder. Between the fervor of the locals and the tourists shifting uncomfortably in their seats, I began to feel like this was something I did not want to see. We left before the final deadly act.

Unsurprisingly, this corridas style of bullfighting, in which the bull is eventually killed, has come under attack over time. Blood sports don’t sit well with modern sensibilities. Arles is one of a handful of places where deadly bullfights still happen, one end of a very long cultural thread. The ritualized slaughter of the bull carries too much meaning to erase, so locals put up strong resistance when bans are proposed. After watching his first bullfight in 1923, Ernest Hemingway commented: “bullfighting is not a sport. It is a tragedy, and it symbolizes the struggle between man and the beasts.” It dramatizes our vexed relationship with other animals, and with the beasts in ourselves.

To heighten the spectacle of this struggle, bulls are bred carefully. Hemingway described one bull he saw as “absolutely unbelievable. He seemed like some great prehistoric animal, absolutely deadly and absolutely vicious.” In the world of the corrida, Hemingway added, “a good fighting bull is an absolutely incorrigible bad bull.” The matadors, on the other hand, strive for perfection, to fight flawlessly. Hemingway commented that “the worst criticism the Spaniards ever make of a bullfighter is that his work is ‘vulgar.’” The dance between the ‘beast’ and the ‘hero’ must be elegant in order to be meaningful art.

The bullfight may be an opposition of man and beast but it is not quite the same as hunting, which is a simpler case of man facing and overpowering nature. A bullfight is a choreographed battle, a moral story played out for an audience which needn’t involve death. The style of bullfight my parents had meant to take their daughters to was the one local to Arles, in which raseteurs jump over the bull and dance around, evading it without actually harming the animal. Further afield, rodeos in the United States serve much the same purpose, as cowboys sit astride bucking steers for as long as they can, risking a trampling. Even small children can try their might against animal power.

Once, in Colorado, I saw the minors’ segment of the rodeo, called ‘mutton bustin.’ Intrepid children clung for dear life onto the backs of panicking sheep, who were let loose to micro-gallop across the sandy enclosure, eventually flinging their riders off like unwieldy sacks of potatoes. The kid who held onto their woolly juggernaut steed the longest was the champion mutton buster.

Why do people need to fight bulls? Why the struggle between man and beast that Hemingway described? We’ve always lived with beasts and on beasts, so we’ve theatrically demonstrated dominance over the creatures close to us. A skillful fight is a very intimate thing. But it’s even more than that. We are beasts. The bullfight is a struggle between man and his beastliness. It’s an eruption of violence, a pressure valve for the eternal problem of what to do with the animal inside, locked in a civilized world. The heroic matador slays a sacrificial bull, representing this inner beast, and the crowd gets a catharsis. This display has created a powerful mythology in bullfighting towns in Southern Europe. Even for those of us who don’t live anywhere near blood-sport arenas, bull monsters still stalk through our imaginations.

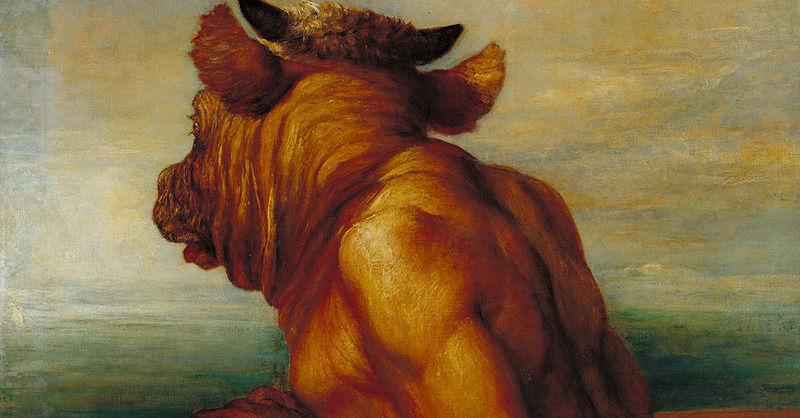

The artist Pablo Picasso had watched bullfights while growing up in Southern France, experiences which embedded the bull and the cult of the matador in his mind. Picasso took the beast in and made it part of himself. He painted not just men fighting bulls, but bull-men.

As Europe felt the ravages of war in the early twentieth century, Picasso produced a series of works linking bullfighting culture with the Minotaur of the ancient world, woven through with his personal mythology. This theme was explored in an exhibition in The Gagosian Gallery in London, Picasso: Minotaurs and Matadors (2017). One of the most famous images, the devastating Minotauromachie (1935), shows a minotaur knotted with muscle looming menacingly above a prone, naked woman. He’s held at bay by a small girl wielding a candle. In some of Picasso’s other paintings, the Minotaur is a protective male force, delicately lifting a limp maiden into a boat; or a wretched one, curling in fetal position, pierced by an arrow, watched by sailing naiads.

The eminent art historian John Richardson, a friend of Picasso’s who died soon after curating the Gagosian exhibition, spoke about the artist’s darker instincts in 2008. He described Picasso’s early mistreatment by art critics, which gave Picasso a taste for torturing them. The artist would etch elaborate designs on a sandy beach, relishing the distraught looks on the faces of the critics as they watched the sea wash the priceless art away.

Picasso was filled with a consuming energy: he wanted to draw out raw emotions from people around him, “a bit like a vampire.” He notoriously wrought havoc on the women in his life, through strings of intense partnerships and philandering. But, like some of the pitiful minotaurs Picasso painted, he was also a “victim of misfortune and tragedy” Richardson pointed out.

Picasso’s minotaurs were a mirror hall of images through which he could look at himself. Oscar Wilde’s Dorian Grey had a painting in his attic to age for him as he indulged his baser instincts. Picasso had a clutch of burly taurine creations to embody the powerful qualities that his small form couldn’t. Sometimes he donned one of the bull headdresses that matadors wore for training to pose for photographs—literally becoming a minotaur. Picasso said himself in 1960: “If all the ways I have been along were marked on a map and joined up with a line, it might represent a Minotaur.” Picasso’s journey as a man left the footprint of a beast.

Not many people think of themselves as half-beasts trapped in human guise, but there’s an echo of the animal in everyone. A beast we each have to struggle with, large or small, trapped and subdued by a maze of modern life. This chapter investigates how we handle our minotaurs, locked carefully in the labyrinths of our minds, and the cost of keeping them at bay.

*

Not long before Picasso was painting his bull-men, the ruins of an ancient palace were being unearthed at Knossos, just outside Heraklion in Crete. The young archaeologist, Arthur Evans, was not the first to excavate there—he followed in the footsteps of several Greek archaeologists. But their origins didn’t suit the heroic twentieth-century narratives of archaeological discovery as well as Evans’s, so he still receives the retrospective limelight.

Evans was familiar with the idea that Knossos might be the site of King Minos’s palace and its Labyrinth. It was a link dreamed up by ancient Roman writers, revived many times over the centuries and widely assumed to be true in early twentieth-century Europe. Evans was initially skeptical of this connection—he knew that it wasn’t even mentioned by Classical Greek texts. But, when he uncovered a set of winding passageways and chambers at Knossos, he couldn’t help himself. In Evans’s imagination, the ruins conjured up the Labyrinth and the palace of King Minos. He named the newly discovered civilization “Minoan,” after the mythical king.

This association would become Evans’s obsession and captivate the minds of archaeologists after him. But visiting Knossos looking for signs of the Labyrinth is a fool’s errand. While the idea is a major source of income for the Cretan tourist industry, no trace of a physical maze has actually been found at Knossos. I knew this when I went to visit. The hilltop site juts into the sky, surrounded by pale carunculated peaks studded with dark trees. It feels like a mythical place. Deep down, I secretly hoped to encounter minotaur spoors and tracks to inspire this chapter. But I might as well have traipsed through the overpriced shopping streets of Capri looking for sirens or sea nymphs.

There is no doubt that the soul of ancient Crete was entangled with bulls, though, just like that of Arles today.

The palace was decorated with frescoes and statues of bulls and balletic human figures vaulting over their writhing, muscular forms. These tokens stoked the flames of Evans’s Labyrinth-hunting. He began to flesh out the story of one of the earliest civilizations of Europe, which had flourished until about 1450 BCE. Crete had traded through the Aegean, Mesopotamia—even as far as Northern Europe—becoming so rich that it dominated all the nearby Mediterranean islands. In early texts, this growing power was credited to the ambition and force of King Minos, but whether or not he existed as an individual, we shall never know.

These ancient stories also mention a dark secret under the King’s palace. A mass of stony passageways winding round and round, folding back on themselves and tangling with one another. From a single entrance, they led to the very center of a maze. It had been built by the cunning craftsman Daedalus, who was the only man capable of making a truly inescapable maze. This Labyrinth housed a creature whom King Minos never wanted to see the light of day, nor to hear spoken of in the palace: his stepson.

The boy’s name was Asterion, which means “the starry one”—ironic given that he had barely seen the skies. He had been born to Minos’s wife, Pasiphaë, the offspring of her fervent lust for a shining white bull. This animal had emerged from the salt-foam of the sea, a gift from the sea-god Poseidon for Minos to sacrifice to him. But Minos had greedily sequestered the bull away in his herds, offering another fine animal to Poseidon instead.

As a punishment, Poseidon filled Minos’s wife with insatiable desire for the white bull. She lingered by the bull’s enclosure, watching his glossy white flanks and sighing with longing. Frustrated by the impossible logistics of inter-species relations, she begged the craftsman Daedalus to help her. He built her a lifelike model cow—hollow and upholstered with cowhide. He took it to the center of a field, helped her into it, and left her to her dubious bliss with her bovine suitor.

Not many people think of themselves as half-beasts trapped in human guise, but there’s an echo of the animal in everyone.

The baby she birthed from this union was a monster, a bull-headed child. But he grew quickly, hidden away, becoming violent and inhumanly powerful. So, Minos plunged the monstrous youth into the dark of the Labyrinth. Only the rumbling reminders of his bellows could be faintly heard through the palace floor. The creature had to be fed, though.

Every nine years, a tribute of fourteen young men and women arrived by ship from Athens, a tax extracted by Minos’s armies. The tributes were feasted and adorned with garlands, showered with splendor for one night. The next day, they trembled as they faced the stone slab of the Labyrinth door. They would only see it once, before the dark swallowed them up for good.

I imagine that Asterion could sense the tributes entering through the twisting passageways. Years of waiting in the crooked dark had sharpened his senses to every small change: the achingly slow growth of cracks in the stone, or the small plumes of dust sent up by the feet of fleeing rats. His eyes were not suited to the dark, but his soft black ears caught the faint echoes of their terror. His wet nostrils drew in each faint scent. The entrance of the young men and women set the stagnant air ablaze with the noxious sweat of fear. He did not need to hunt them down—they would come to him. Each path in the Labyrinth led to its center, disorientating the victim as they fled—drawing them straight to what they feared.

Twenty-one years after he was locked away, the Minotaur heard a third grinding slam of the Labyrinth door. He smelt the familiar terror. Yet amidst the fear was something else: intent. He felt rage tinged with foreboding for the first time. Something was coming for him.

It was Theseus, son of Poseidon, stepson to the King of Athens, set on freeing his people from Minos’s tyranny. He held a prize that would save him from the Labyrinth—a simple clew of blood-red thread given to him by Asterion’s beautiful half-sister, Ariadne. She had fallen for the young prince as he danced at the feast the night before, and had resolved to save Theseus from his bloody fate. Pressing herself close to him, as drunken revelers cavorted around them, she had wrapped him in her warm scent and folded his fingers around the clew. A promise of freedom—as long as Theseus took her far away with him.

As the other Athenians cowered by the door the next morning, flinching from the shadows of the maze, Theseus tied the end of the thread tight and unwound the clew beside him, pacing into the dark. The bright filament traced his steps to the beast’s lair and—blood-soaked and victorious—led him back out into the light again. The youths wrenched the door slowly open, and the fourteen figures stole off into the night to the harbor. In the dark of the maze, a black heap lay still on the sandy floor in the centre of the Labyrinth. Asterion’s eyes clouded over and slowly dulled.

__________________________________

From Enchanted Creatures: Our Monsters and Their Meanings by Natalie Lawrence. Copyright © 2025. Available from Pegasus Books.