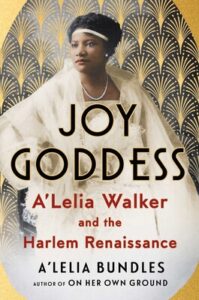

Poet Langston Hughes crowned my great-grandmother A’Lelia Walker “the joy goddess of Harlem” because of her fabulous parties and friendships with Harlem Renaissance writers, artists and actors. Today she is best known as the only daughter of Madam C.J. Walker—the early twentieth century beauty industry pioneer and millionaire philanthropist—but during the 1920s she was an internationally famous heiress and a legend in her own right. Black newspapers chronicled my grandmother Mae Walker Perry’s elaborate 1924 wedding and fancied her as a black Cinderella.

Article continues after advertisement

But long before I grasped the Walker women’s historical significance, I had felt their presence in more intimate ways. At home, our silverware was monogrammed with the letters “CJW” and the Chickering baby grand piano on which I learned to read music had been played by famous musicians in A’Lelia Walker’s Harlem apartment.

While those vintage artifacts embodied a universe of untold tales, I’d never found such stories—or stories about anyone who looked like me—in the books of my early childhood. As an elementary school student during the 1950s and 1960s, I loved the mesmerizing fictional worlds in novels like Madeleine L’Engle’s A Wrinkle in Time, but I also was intrigued by the nonfiction narratives of accomplished women like pilot Amelia Earhart and author Louisa May Alcott. Missing, though, from the shelves of my suburban Indianapolis school’s well-stocked library were Mary McLeod Bethune, Harriet Tubman and Phillis Wheatley, the only black women in Bobbs Merrill Publishing Company’s 186-volume children’s biography series.

I now know that my Walker biographies place me in a long tradition of black women who have written about their female forbears.

Fast forward a few years later and I am the only black student in my American history honors class in my large, predominantly white public high school. The day’s topic is the Civil War. And my body is stinging as prickly flares of embarrassment radiate from my ribs. Deep down, I know that this isolating, fiery shame is not justified. But as a teenager, I do not know how to extinguish it.

On this day, as we review a new chapter, my eyes lock on a section titled “Negro Slavery,” the only reference all semester to people of African descent. The boldface letters glare from the page. Then I read a paralyzing sentence that says “slaves” were “contented.”

Years later when a friend helps me track down Henry Bragdon and Samuel McCutchen’s History of a Free People, I am stunned once again by their dishonestly benign notion that “slaves…were seldom cruelly treated” since it was “to the interest of the master to keep them healthy and contented.” Even as they conceded that slavery was “a horrible episode in the story of ‘man’s inhumanity to man,’” they claimed that “the freedman was sometimes worse off than the slave.”

I knew in my soul this paragraph was a lie, but in high school I lacked sufficient evidence to refute it. I now know that we were being taught Lost Cause propaganda contrived during the early 1900s by the United Daughters of the Confederacy and a group of prominent American historians who’d methodically injected a narrative of white supremacy and black inferiority into American history textbooks. Such a curriculum left no room for discussion about abolitionists Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman and precluded any mention of the rebellions mounted by enslaved people who surely were not contented or of my free-born North Carolina ancestors who served as Continental Army soldiers during the Revolutionary War.

Fortunately, at home and in my neighborhood I was surrounded by black role models. Whenever I accompanied my mother, A’Lelia Mae Perry Bundles, to her downtown office at the Walker Building, I saw a woman who moved confidently as vice president of the hair care company her great-grandmother had founded in 1906. And while she had majored in chemistry and business at Howard University to prepare for a career as a Walker Company executive, she and my father encouraged me to pursue my passion for writing.

Even as I enjoyed a 30-year career as a journalist—first as a producer with NBC News, then as a producer and an executive with ABC News—the pull of the Walker legacy remained powerful. In high school, I’d written a report about A’Lelia Walker and the Harlem Renaissance. In college, I stumbled upon W. E. B. Du Bois’s laudatory Crisis magazine obituary of Madam Walker, but I still wasn’t ready to fully engage with this part of my heritage.

Then during the fall of 1975 at Columbia University’s Graduate School of Journalism, after my masters project advisor Phyl Garland listened patiently to my pitch of uninspired topics, she finally spoke. “Your name is A’Lelia. Do you have any connection to Madam Walker and A’Lelia Walker?”

Because she was a long-time reporter for Jet and Ebony, I suspect she knew the answer, but I rarely volunteered that information.

“Umm, yes, that’s my family,” I answered.

“Well, that’s what you’re going to write about!” she declared.

Phyl’s enthusiastic interest validated the significance of the Walker story and began to frame my role in telling it.

A few weeks later, I traveled to Indianapolis where my mother was being treated for terminal lung cancer. Although she was weary from chemotherapy, she seemed excited about my topic. When I asked how I should handle any flaws or controversies I might discover, she leaned forward in her hospital bed and said “Tell the truth, baby. It’s all right to tell the truth.”

In what would turn out to be one of our last conversations, she granted me permission to be candid and honest, and bestowed a gift that has allowed me to write authentically.

I now know that my Walker biographies place me in a long tradition of black women who have written about their female forbears from Alfreda Duster, who edited her mother Ida B. Wells’s autobiography, Crusade for Justice, to dozens of others who have been compelled to delve into the details of their family sagas. With each generation—whether their stories are published or not—our elders insinuate themselves into our consciousness and insist that they not be forgotten. For our enslaved ancestors who risked being whipped or sold for knowing how to read or write, simply being literate was a subversive act of rebellion and militant self-expression. Whether it is Phillis Wheatley’s poems or Ashley’s embroidered sack, the deep need to assert one’s humanity remains irrepressible.

At a moment when it would be tempting to be pessimistic and discouraged, I’m more committed than ever to follow my mother’s advice to tell the truth.

Before 1970—and in some university history departments long after 1970—dissertation proposals about black women’s lives and concerns were often rejected as unworthy of scholarly study. But in response to the fervor of the Civil Rights Movement and the Women’s Movement, some universities began to embrace serious scholarship about their businesses, civic organizations, art and political activism. For more than fifty years that research has spawned thousands of books, documentaries, museum exhibitions, plays, apps and social media posts. As a result, stories that had been erased, sanitized and ignored are now ubiquitous in American culture.

But today the backlash to that progress is fierce and punitive as presidential executive orders mandate the removal of books from military base libraries, prohibit words like activism, equality and bias on federal agency websites and accuse the Smithsonian Institution of fomenting what the White House has ominously deemed “improper ideology” in exhibitions that finally present a more nuanced account of America’s racial past.

I cannot pretend to know what is in the hearts and minds of the people who are leading the crusade to ban books and who are dismantling agencies that fund libraries and arts organizations, but I know from my own experience what it means to be a child who does not see herself in books. I know what that absence suggests to her and to her classmates: that her story does not matter, and even worse, that there is something wrong with her and with people who look like her. It also consigns her classmates to ignorance.

At a moment when it would be tempting to be pessimistic and discouraged, I’m more committed than ever to follow my mother’s advice to tell the truth. I do so with the hope that my books might inspire some young high school student as she discovers her purpose and seeks her place in the world.

__________________________________

Joy Goddess: A’Lelia Walker and the Harlem Renaissance by A’Lelia Bundles is available from Scribner, an imprint of Simon & Schuster.