Every time a new film adaptation comes out, as each year it inevitably does, the same questions come. Aren’t we sick of these stories? Aren’t there other heroines, less white, less privileged, who deserve our attention?

Article continues after advertisement

But still Jane Austen retains her extraordinary hold.

Perhaps it’s because her books work on so many levels. You can read them as upbeat romantic comedies. Or maybe you prefer to think of them as balm to a troubling world, because virtue gets rewarded. Or you can—as I choose to—read these novels for their bitter hidden message. For me, they’re stories that utterly condemn a society in which women like Jane Austen herself were expected to marry for money.

When I ask people to name their favorite Jane Austen novel, the answers are often revealing. If Pride and Prejudice gets mentioned, I smile, because of course I love it too. But secretly I think of it as only entry-level Austen, and often I detect in people’s choice of it the influence of Colin Firth in a wet shirt. But I also envy those people. For them, the best is yet to come, in the form of the later, greater novels like Mansfield Park.

Many Austen lovers describe themselves as having “graduated” to Persuasion, the last of the novels completed before the writer died. Perhaps you can’t quite appreciate it fully before your own middle age, for it’s really about the beauty of getting a second chance at life and love. It’s sobering to realize that Anne Elliot, the heroine, who’s perilously close to what Jane Austen calls “the years of danger,” and of being “left on the shelf” as a spinster, is in fact in her late twenties.

In private, to her sister, she could admit the truth: “I write only for fame.”

One of Jane Austen’s friends thought that Anne was the heroine whom the author most resembled in real life: sweet and self-effacing. That may well have been how Jane Austen’s family liked to see her. But her private letters to her sister Cassandra show a sharper and more astringent person, someone whose cruelty and bitterness were redeemed only by her jokes. My own favorite Jane Austen character is the one she described as “a heroine whom no one but myself will much like.” Emma’s Emma Woodhouse is rather difficult and uppity, which is in fact precisely why I like her so very much.

The sad truth is that even the sparkling Lizzie Bennet struck many of Jane Austen’s early readers as offensively uppity. Of course, in Jane Austen’s lifetime, none of her published books had her name on their covers. That would have been unladylike. This reticence also partly explains the questions we have about her physical appearance, despite the fact that she’s depicted on the British £10 note. The image used there is one that her publishers had to rustle up posthumously, once her sales were really beginning to catch fire, to satisfy the readers who wanted to see the face of their favorite author. Cassandra Austen’s hasty and incomplete sketch of Jane survives in the National Portrait Gallery in London. Apart from that, though, it’s poignant to think that no one in her lifetime cared enough about what Jane Austen looked like to commission a proper record.

Born in 1775 in her father’s rectory in the Hampshire village of Steventon, Jane Austen came from a rank in society helpfully described as the “pseudo-gentry.” This means her family aspired to belong to the landed gentry, but didn’t actually own any land. Living like a gentleman on the income from a not particularly prosperous parish, like her father did, involved a certain amount of keeping up appearances. And just like Mr. Bennet in Pride and Prejudice, he saved nothing to leave his daughters after his death. If she didn’t marry, Jane Austen was destined to live as a poor relation, clinging on to gentility through the charity of friends and the wider family, who expected her to provide cheap childcare for her thirty-three nieces and nephews.

And that’s why I’m attracted to the subversive suggestion that even though these are some of the greatest novels about courtship ever written, her stories don’t truly celebrate marriage.

This pseudo-gentry status meant the Austens would have found it socially inappropriate if Jane had ever wanted to go out and get a job. She could have worked as a governess, for example, earning £50 a year. Instead, she had to manage on the £20 a year pocket money given her by her father—or else do what he expected her to do, which was to marry money.

I’d argue that the most important moment in Jane’s life was December 2, 1802. That day, she accepted an offer of marriage, from a man with a mansion and a fortune. But that night, she decided to break it off. She just couldn’t go through with it. We never get her own explanation for why she made this choice. But for me it lies in the timing, because at this point in her career she had just sold her first novel—the one that would become Northanger Abbey—to a publisher. For £10. Not a lot of money, but it changed everything. I think it gave her the courage to turn down status and stability, to try to live as a professional writer instead.

And that’s why I’m attracted to the subversive suggestion that even though these are some of the greatest novels about courtship ever written, her stories don’t truly celebrate marriage.

When Jane Austen approaches the moment her heroines finally get engaged, it is possible to argue that something a little strange happens to her storytelling. If you look at the exact moments where matches are made, you may find them a little abrupt, almost perfunctory. We don’t hear Emma Woodhouse accepting Mr. Knightley’s proposal. We don’t see Edmund falling in love with Fanny Price. Charlotte Lucas in Pride and Prejudice is perfectly open about the fact that she’s marrying not a man, but a lifestyle, as the mistress of an establishment of her own. And in the very final paragraph of Mansfield Park, the object of Fanny’s affections is not a person so much as a property. It is Mansfield Parsonage, not her husband, that she now finds ‘as dear to her heart’ as anything.

Perhaps Jane treated these events lightly, almost mechanically, because she didn’t really believe that a man, on his own, could bring a happy ending. What her heroines need as much as love is financial security.

I think that Jane Austen herself paid more attention to her sales and her income as an author than her family cared to know. Early guardians of her legacy, the Austen family liked to think of her as a “good little woman” who wrote her books almost accidentally, with no apparent effort, “St. Aunt Jane of Steventon-cum-Chawton Canonicorum,” as she’s been called. A woman who’d never have wanted her name on the covers of her books anyway.

How little did they know her. In private, to her sister, she could admit the truth: “I write only for fame.”

She completed her last three novels during the happiest time of her life, living with Cassandra in the Hampshire village of Chawton. She left it only to seek medical treatment for an illness which still remains mysterious, and which killed her at the brutally young age of forty-one. Her family buried her in Winchester Cathedral under a stone with an inscription that—famously—makes no mention of her books.

But in subsequent decades, as her books caught on, people started to know her name.

Today, 250 years after her birth, Jane Austen has got what she secretly wanted. A name of immortal fame.

__________________________________

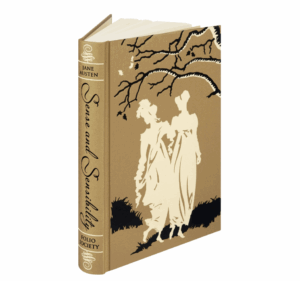

Foreword by Lucy Worsley for The Folio Society’s Limited Edition of Jane Austen’s Complete Novels. Available 4pm BST 9thSeptember.