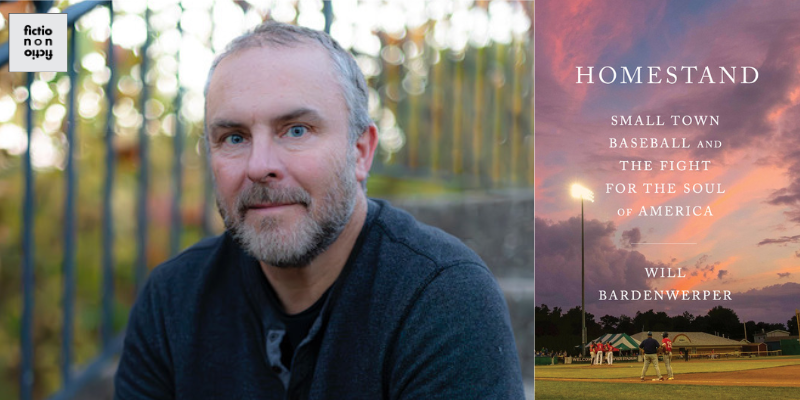

Journalist Will Bardenwerper joins co-hosts Whitney Terrell and V.V. Ganeshananthan to discuss his new book, Homestand: Small Town Baseball and the Fight for the Soul of America, which explores the consequences of Major League Baseball cutting 40 affiliated minor league teams, each one only as expensive as an average Major League salary. He explains how the accessibility and affordability of minor league baseball has made it a unique gathering point for working-class communities like the one in Batavia, New York, where Bardenwerper followed the local team, the Muckdogs, for a season. He celebrates the traditions and resilience of the Muckdogs fans and owners, who revived the team after it was eliminated as a minor league franchise. He also reads from Homestand.

To hear the full episode, subscribe through iTunes, Google Play, Stitcher, Spotify, or your favorite podcast app (include the forward slashes when searching). You can also listen by streaming from the player below. Check out video versions of our interviews on the Fiction/Non/Fiction Instagram account, the Fiction/Non/Fiction YouTube Channel, and our show website: https://www.fnfpodcast.net/ This podcast is produced by V.V. Ganeshananthan, Whitney Terrell, and Moss Terrell.

Homestand: Small Town Baseball and the Fight for the Soul of America • “Minor Threat: MLB puts the farm system out to pasture” by Will Bardenwerper |Harper’s Magazine • The Prisoner In His Palace: Saddam Hussein, His American Guards, and What History Leaves Unsaid

Others:

Fiction/Non/Fiction Season 3, Episode 4: Wild Ecologies: So Go the Salmon, So Goes the World: Tucker Malarkey, Will Bardenwerper, and Stan Brewer In Conversation • Moneyball by Michael Lewis • Field of Dreams (1989) • Shoeless Joe by W.P. Kinsella

EXCERPT FROM A CONVERSATION WITH WILL BARDENWERPER

V.V. Ganeshananthan: So Ernie Lawrence, who we’ve discussed, appears in that passage, and he’s in the bleachers reading a biography of Stalin, as one does at a baseball game. It’s the capacious space that these ballparks are making for people who are not always lonely but may be sometimes lonely, not exactly loners but maybe, as you said, not the most extroverted. There’s a pleasant in-betweenness and there’s something profoundly American about reading a book, educating yourself at a baseball game. I was reading this, and I was comforted to know that I’m not the only person who takes a book to a sporting event. Is that part of the peace you’re talking about, that space to educate yourself and take some time to do something like read a book at a baseball game?

Will Bardenwerper: There’s a lot going on there. There is something about the pace of baseball, and I wasn’t the first one to observe this or write about it, but it’s different from football or hockey or basketball, where it’s this feverish, breakneck thing. You’re not going to have a leisurely conversation at a hockey game or a basketball game. There’s just too much going on, the action’s too fast. With baseball, particularly at this level, you can have conversations that last for games, for weeks. You talk to someone for a few innings, then you may go your separate way, and then the next night, you run into the same people, and you pick up where you left off. That’s what’s unique about baseball at this level, as opposed to the Major League level.

I think too, it’s worth noting that, because it’s so cheap—it’s $99 for a season ticket— because it’s logistically so easy to get to—it’s nestled in a residential neighborhood— you have 80-year-olds. I mean, it’s difficult for an 80-year-old to get to Yankee Stadium, much less to park, to get to seats up in the upper deck. That’s beyond the capability of probably a lot of people that age here. I write about Bill Kauffman’s parents, who are in their mid-80s. They go every night because it’s two blocks away. They walk in and they’re in their seats five minutes later, and they can leave as soon as the sun goes down and it begins to get chilly. And there’s an intergenerational element to it. For that same reason, you have grandparents, their kids and their kids’ kids all together. There aren’t really that many places where that occurs in American life today, besides maybe Thanksgiving dinner. Here you have this happening every night. It’s oftentimes the same people, and that contributes to that ability to have these relationships evolve and mature over time. There’s a leisurely element to it that you wouldn’t find surrounded by 70,000 screaming strangers at a Major League sporting event.

Whitney Terrell: One of the things that I thought about a lot in this book, because you have a lot of characters, there’s a whole Dramatis Personae in the beginning, and you talk about the broadcaster John Carruba, and all these other people that you meet—the guy who shags foul balls outside of the stadium. I was reminded of this concept, which is a real one in American life, that it’s okay to just live in your town and be important within the history of your town. You don’t have to be important nationally. You don’t have to even talk to anyone outside of the town. The town is a self-enclosed encapsulation of time and people know the town over time. I wonder if that is something that we’re losing. Because on social media, for instance, you have to be talking to everyone in the world, right? You have this illusion that you need to be important there instead of within the town that you live in. I wonder what you think of that idea. And I just wanted to point out that they also have a John Gardner Night, which I thought was pretty awesome, probably the only one that I’ve ever heard of.

WB: I’ve unfortunately not made it to John Gardner Night. Often, I think it’s around Halloween, and I have two young kids, and Halloween is one of the biggest holidays of the year when you have young kids. So I have not made it to John Gardner Night, but Bill tells me that I really need to get there for one of them. That’s on my to-do list. I think he said, “We don’t even really like John Gardner, but he’s ours, someone needs to remember him, and so it’s our duty to do so.” There was something comforting about that, it was nice. I grew up in D.C. I lived in New York for a long time, and I liked the sense that, that you’re right, you can inhabit a valued place in this smaller ecosystem.

To some extent, there was an element of escaping that social media world that can take over our lives. That, of course, can occur just as easily in a small town as in a big city. But at least in the writing and journalism world, we’re uniquely susceptible to being held hostage by it. It was nice to get beyond that. The ballpark was a place where you could put your phone down for at least a little while. Two of the people that were the happiest people, as a matter of fact, Ernie Lawrence and Bill Kauffman, who I write about, the one commonality was neither of them owned an iPhone. There may be something to that. There was actually one night where Bill said, “I’m going to be at the game tonight.” I thought “Okay, I’d love to get together.” I get to the ballpark, and I keep calling his number, and no one answers. And I thought “I swear he told me he was going to be here,” and then I bumped into him, and I said, “Bill, I’ve called you a dozen times. How come you didn’t pick up?” And he’s like, “Well, I have a landline. It’s ringing probably at home but I’m here.” It never even occurred to me that there’d be someone that gave me a phone number and then did not actually have the phone that I was dialing.

VVG: Will, you write, and I’m quoting from the book here, “The decision by billionaire Major League owners to extinguish these community ball clubs, some of the few remaining places where people could still find happiness and connection for affordable prices, as they had for generations, merely to save the equivalent of one major league minimum salary, struck me as emblematic of so much of what was wrong with today’s America.” You go on to ask if this is the set of values that “we as a country were fighting for, that some of my friends had died for.” So what is the future for minor league baseball and baseball in general? What can the sport do to rebuild and reclaim a connection to these values, this precious space that we’ve been discussing?

WB: I think there’s a number of things. Baseball is a microcosm for socioeconomic forces that we see extending into any number of elements of our lives. When it comes to baseball, it’s important to recognize, I realize this is a capitalist country, and they’re entitled to make whatever business decisions they want. But what bothered me in particular, with what they were doing, was the tendency they have to pretend to transcend business: “We’re America’s pastime. We inhabit this elevated space that is beyond even business.” You watch their commercials, and there’s always, you know, the families playing catch in the cornfield and this Norman Rockwell Americana that they certainly latch onto for marketing reasons. But then you see the decisions they’re making, which are ruthlessly McKinsey-inspired, trying to extract every last dime for return on their investments.

This was highlighted wonderfully or terribly, depending on how you look at it, by this Field of Dreams game that they stage out in Iowa. They put on a Major League game at the ballpark that was built for the Kevin Costner movie, Field of Dreams. And it’s this ode to Americana and to baseball’s historic role in our country. But when you dig down, you realize that everyone at the game, or most of the people, are wealthy people from the Coast who fly there, buy the tickets that are thousands of dollars on the secondary market. And at the same time, they had cut two actual Iowa teams that were in the minor leagues that were a few hours away. How do the people that actually live in Iowa benefit from this? Now there’s one game of summer that they can’t afford, and the two teams that they could go to every night were cut to save a little bit of money.

It’s that hypocrisy that frustrated me the most, and as far as what we can do to preserve baseball, and, more broadly, to fight back against these economic forces, I think the first is to just appreciate what we still do have and to support those businesses, whether it’s a ball team or a local independent bookstore. Because I’m not arguing that baseball is like the only place where we can have this community spirit and where people can come together. I think there’s any number of other places, like a local independent bookstore, going there, when there’s an author in town doing a book signing. I was talking to the lady who runs our independent bookstore in the town I live in, and she said, “People always come in and say, ‘Oh, we’re so glad you’re here. We love having an independent bookstore.’ But then we’ll have an event where an author shows up and two people from the town go buy a book.” If we want these places to survive, we have to put our money where our mouth is and support them, whether it’s a ball team, a bookstore or somewhere else that provides people a chance to come together so that we’re not left in a society where there’s 10 baseball teams with players making a billion dollars, or there’s 10 authors that sell their books on Amazon or 10 movies—Avengers Version 25. If we want some degree of local businesses and local culture and local arts and local sports to survive, it’s going to take a concerted effort to actually support them.

Transcribed by Otter.ai. Condensed and edited by Rebecca Kilroy. Photograph of Will Bardenwerper by Jaxon Fox.